The torrent of trade tariffs announced by Donald Trump since the start of April will obviously have widespread ramifications for institutions and individuals around the world – but to what extent should all this matter to investors? Less than you might first imagine is our answer – and if that sounds too contrarian, even for committed value investors, please do bear with us.

The main reason we hold this view is because the implications of the US president’s tariffs fall into the bucket marked ‘important but impossible to predict’. Not only do we not know how companies and governments will respond to the tariffs, we have no way of knowing how long they will be in place, nor what the second and third-order effects might be. Indeed, despite what the many talking heads in the media are saying, nobody does.

As value investors, then, how do we deal with this uncertainty? By doing what we always do and maintaining a healthy ‘margin of safety’ in every investment we hold. As discussed in pieces such as When a crystal ball isn’t enough, we achieve this by only holding companies that are trading at a significant discount to their fair value and ensuring they have sufficient balance-sheet strength to see them through whatever the future may hold.

When building portfolios, we also aim to incorporate as many idiosyncratic drivers of risk and return as possible. While very few companies will be immune to the unfolding global trade war, we invest in businesses that are undervalued relative to their long-term earnings potential. Put another way, the main driver of returns is what is happening within the companies themselves – not the US president’s evolving take on tariffs.

Opportunity or threat?

That is not to say that, writing this in late April, we think the extreme market moves of recent weeks do not matter. They do, of course, as they increase the probability of a recession, as companies hold back on investment, orders are deferred and consumers become more cautious. As such, we need to be vigilant with regard to balance sheets and ensure valuation headroom is sufficient to protect against a potential downturn.

If we are looking for a silver lining here, it is perhaps that – for once – the UK feels relatively well-positioned compared with many other parts of the world. The tariffs imposed are a relatively modest 10% or thereabouts and the starting valuation for many UK-listed companies is already so low that a recession has effectively been priced in. The market might punish them twice but, to our mind, that would merely make them twice as cheap.

“A notable aspect of this crisis is the market’s view of it as universally bad – yet rarely in economics is that the outcome. What harms one party often benefits another.

Not only do we not know how companies and governments will respond to the tariffs, we have no way of knowing how long they will be in place, nor what the second and third-order effects might be. Indeed, despite what the many talking heads in the media are saying, nobody does.”

Goods exported from the UK to the US only account for around 2% of UK GDP and the Labour government has already announced some countermeasures for key sectors such as automotives – for example, relaxing electric vehicle requirements. The actual impact should therefore prove to be less severe than the recent share-price declines would suggest.

Another notable aspect of this crisis is the market’s view of it as universally bad – yet rarely in economics is that the outcome. What harms one party often benefits another: excess supply in one market means lower costs for others; producers in protected US markets will likely benefit from better pricing – even if it means higher costs for consumers; the net effect on global GDP may be negative, but there will undoubtedly be winners and losers.

‘Epistemic risk’

Another lens through which to view the current panic is the difference between risk and uncertainty: we have known tariffs were coming for some time – it is just the specifics that were a surprise. This is a classic case of ‘epistemic risk’ – where decisions are based on flawed information, assumptions or misunderstood dynamics. It is not the randomness of markets that causes it, but the danger of believing something that turns out to be false.

Market participants could not have known what tariff levels Trump would introduce so the question now becomes: is epistemic risk higher or lower after the tariffs have been announced? And you could certainly make the case it is lower. The tariffs have been revealed. The methodology is clear – up to a point. And, while we still do not know the long-term effects – well, that was just as true before the announcement as it is now.

Arguably then, we now have more information and less uncertainty than we did before ‘Liberation Day’ on 2 April. Even if that were not the case, when it comes to equity investing, ‘unknown unknowns’ tend to overwhelm specific risks over the long term. If there is one mistake the market seems to make consistently, it is under-pricing unspecified, unknowable risks – and over-discounting known, specific risks.

So is this good news for value investors? Maybe. It certainly reminds the wider market the future is unknowable – and valuation and balance sheets still matter. At times like this, investing based on momentum, in companies with full valuations, offers limited protection against uncertainty. Although we cannot predict the future, it helps to consider what the market may be pricing in – and judge how pessimistic or optimistic that sentiment truly is.

Focus on fundamentals

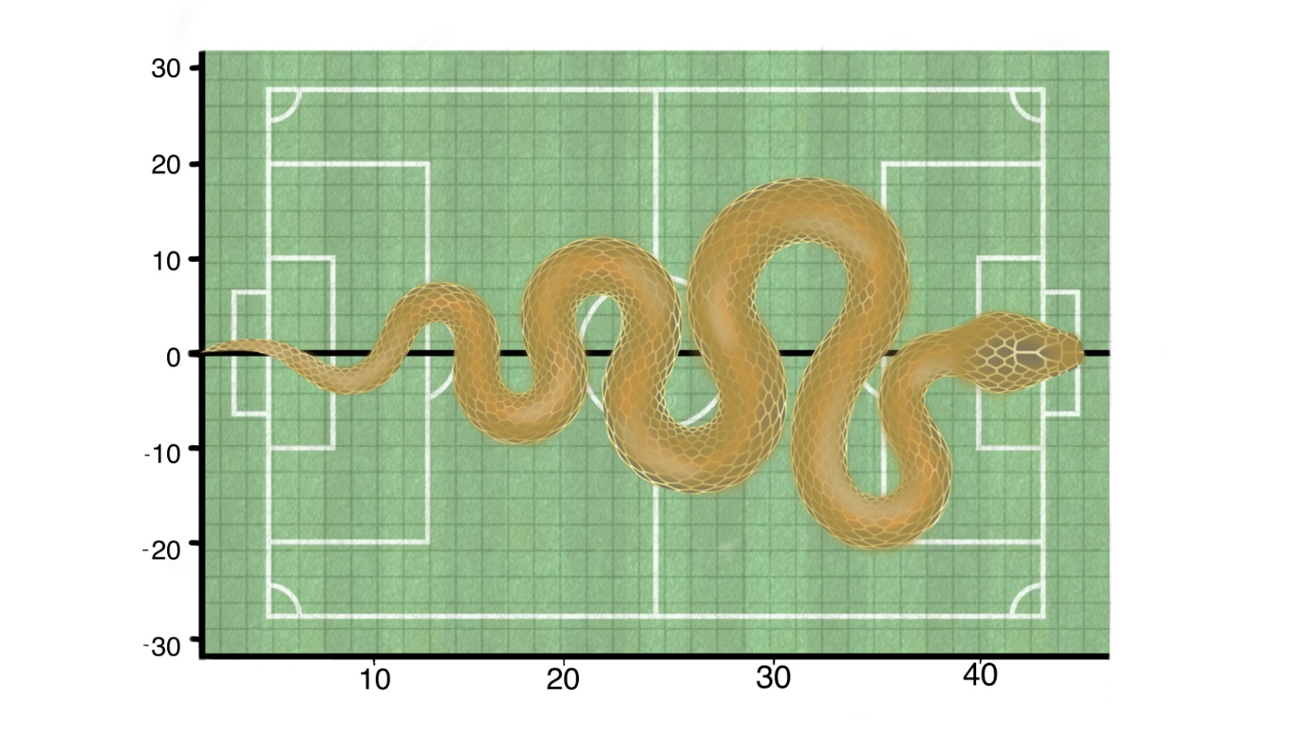

Let’s end on some numbers for context: in 2024, the UK exported £59bn-worth of goods to the US – about 2% of GDP. Since ‘Liberation Day’, the FTSE All-Share has declined 11%. For a company with no growth, about 75% of its value lies in cashflows beyond five years. Thus an 11% drop suggests either permanent profitability is 11% lower or profits are wiped out for three years – or some combination of the two. That feels overly harsh.

Looking through the lens of US GDP, meanwhile, Trump’s goal is to close the trade deficit, which is currently around 4% of US GDP – roughly $1tn (£755bn) or about 1% of global GDP. Total goods imported into the US represent 11% of US GDP. So, if all imports stopped – which would be extreme – global GDP excluding the US would fall by 4%. Yet the MSCI World ex-USA index is down 11%. Again, that seems a severe overreaction.

There is an ancient Persian adage – later attributed to King Solomon and referenced approvingly by another US president, Abraham Lincoln – that acts both as a warning against being too optimistic when things are going well and as a comfort when life seems to be going against you. If that did not already make it a perfect motto for value investors, it goes further still by neatly encapsulating the idea of mean reversion in just four words.

It is ‘This too shall pass’. Markets can and do overreact in the short term. But tying share-price moves back to fundamentals – and holding to our evidence-based process grounded in well-established principles – gives us confidence that prices will recover. Ultimately, this is just another in the long line of ‘crises’ we have all had to navigate in our lifetimes. And this too shall pass.

Tom Grady is a fund manager and research analyst on the Value Team at Schroders and a contributor to The Value Perspective blog