Accurate, comprehensive data is a wonderful thing! It makes due-diligence more robust and gives confidence in decision-making – not to mention ticking some of The Consumer Duty boxes. Sometimes though, data analysis can raise as many questions as it answers. Not to worry, good data can also answer those questions or at least arm you with your own set of questions for asset managers as you go through a selection process.

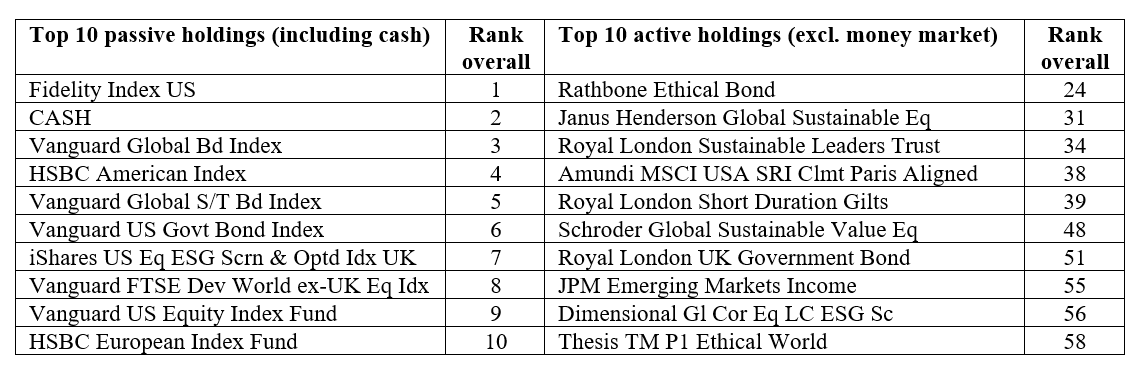

Let me give you an example. At Defaqto, we recently completed some analysis on what MPS portfolio managers were currently buying and holding. We looked at average asset allocation across the whole MPS portfolio universe – on platform, unweighted – to determine the most commonly held underlying investments. The results are shown in the following table:

“In short, look at the holdings and look carefully at the costs when determining your selection shortlist.

Source: Defaqto

Two things leap out at you straightaway here. First, all of the top 23 holdings are either index funds or cash funds. Second, with one exception, all the top active funds are ESG/ethical or gilt funds. You might also raise an eyebrow at the most popular non-ESG equity fund appearing at 55th on the list! And you might well wonder how, given three-quarters of MPS portfolios are listed as primarily active portfolios, why the dominance of index funds?

To a certain extent this can be explained away in that most active portfolios will have some index fund exposure to either help reduce costs or because the index play is the best way to cover that segment of the market. And yet, while there are an abundance of index solutions to choose from, it appears DFMs generally flock to the usual suspects, whereas in the active space, it is far more down to personal preference and due-diligence. With index trackers being so prominent – frequently replicated across not only a DFM’s range but also found in the competition’s range – how does a DFM make themselves stand out?

Overriding question

Too late though – the seeds of doubt have been sown (and rightly so). We would probably all accept that most portfolios will have some index trackers in them – either to access markets where there is little information or, conversely, where analysis has been done to death and beating the market becomes much more difficult. The overriding question for advisers and their clients, though, should be: Am I paying too much for my active portfolio?

There is of course an argument that getting the asset allocation right is the key to good outcomes – regardless of whether the underlying funds are trackers or actively managed. Maybe so, but it is indisputable that in-depth research on active managed funds is costlier than research on trackers – so charges should be lower.

Without going down the ‘Which is best – active or passive?’ wormhole, if you believe in active management, and are prepared to pay for it, you do not want a portfolio with too many trackers. You are paying for the skill of the portfolio manager in selecting active funds.

While there are an abundance of index solutions to choose from, it appears DFMs generally flock to the usual suspects, whereas in the active space, it is far more down to personal preference and due-diligence.”

Each individual adviser will have their own opinion on what is fair and will have to exercise their own judgement – for example, is 10% or 20% OK in trackers? As a guide, the average cost of an active portfolio from the Defaqto Comparator Balanced peer group is 0.82%. For a portfolio made up of trackers the average total cost is 0.35%. So you are paying, on average, 50 basis points more for active management.

We classify passive portfolios as those that, excluding the cash element, contain at least 90% in trackers. There may be a big gap in what is acceptable to the point where we classify them as passive portfolios. In short, then, look at the holdings and look carefully at the costs when determining your selection shortlist.

Smaller pool

There is probably a similar thing going on with the active funds in that there has been a boom in growth of ESG related funds and, again, there is a smaller pool of underlying funds to choose from, so the same names keep popping up.

This probably also underlines the argument that selecting active funds is more difficult and therefore costly. It should also be noted the average total cost of an ESG/ethical portfolio is very similar to that of active portfolios as a whole. The same rule applies, however – look at the holdings and make a judgement on whether the weighting of trackers in the portfolio makes you think you are paying too much for active management.

Finally, you would expect the words ‘index’, ‘passive’ or ‘tracker’ to appear in the portfolio name if it was a passive portfolio you were looking for. Perhaps we can excuse the likes of Vanguard for not doing this as they are well known for passive portfolios – for the large part, it is what they do.

These aside, of the 561 portfolios officially recorded as being passive within the Defaqto Engage adviser research software, 269 do not mention their passive style in the name. I know the majority are passive – but it is not certain. This means that due-diligence has to include a follow-up question: ‘Is this a passive portfolio?’ – or they could get dismissed from the process up front, on an ‘If in doubt, leave them out’ basis.

The good news is, the data is available. So make sure you know what you are buying, that it reflects clients’ preferences and that a fair price is being paid for the management of the portfolio.

Andy Parsons is head of investment & protection at Defaqto