In case anyone was worried all the excitement of last year was just a blip, 2026 has kicked off with plenty of drama. It suggests another noisy year ahead for geopolitics and, potentially, for stockmarkets – though investors will be happy enough if it also brings about another 12 months of double-digit gains. Either way, they are likely to face a series of pressure points over 2026 – and these five look set to be among the most significant.

1. US inflation

US inflation could be the most significant swing factor in 2026. The data has been difficult to read – not helped by the US government shutdown for a chunk of the fourth quarter – with inflation persistently above expectations for much of 2025, but then apparently trending lower in the final months of the year.

On the one hand, it should not be possible to deliver GDP growth at above 4%, impose tariffs on imported goods, loosen fiscal policy and cut interest rates without some sort of inflationary response – yet inflation has still to reach problematic levels. Economists have attributed this to some stockpiling ahead of tariff changes and a weaker dollar, but this does not feel like a full explanation.

If US inflation starts to rise, all bets are off for financial markets. Even Donald Trump cannot avoid the grim judgement of bond markets, nor the likely associated sell-off in equity markets. This could be the trigger event that finally interrupts the bull market and prompts investors to question valuations.

Nathaniel Casey, investment strategist at UK wealth manager Evelyn Partners, believes evidence of tariff impacts is creeping into the inflation data. “Core goods inflation has accelerated from 0.3% year-on-year in May to 1.5% year-on-year in September,” he points out. “Within this, the basket for apparel – an import-sensitive segment – accelerated by 0.7% month-on-month in September, its highest rate since this time last year.”

An attempt to dampen inflation may have been a swing factor in Trump’s intervention in Venezuela. As discussed in this week’s Monday Club, the crude – pun intended – calculation is that Venezuela has lots of oil and removing a problematic president could help bring that oil on-stream, depressing the oil price and cutting inflation.

There are problems with such a calculation, however: oil supply could weaken rather than strengthen as a result of the US’s actions, while Venezuela’s productive capacity could take years to increase. Trump may lean on US companies to invest in the region; equally shareholders may revolt at uneconomic investment in Venezuela rather than alternative options.

The appointment of the new Federal Reserve chair may also be influential for inflation expectations. If, as expected, Trump appoints someone who shares his desire for lower rates, there is a question as to whether they will keep rates low even in the face of higher inflation. The prevailing view is that any Fed chair may become acutely aware of their potential legacy once in office – and thus disinclined to take the reputational hit of previous monetary doves such as Arthur Burns in the 1970s.

“The big promise of AI is that it can deliver productivity benefits for companies – or, to put it another way, replace costly humans with far less troublesome tech.

2. AI versus jobs

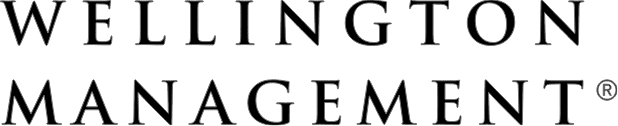

Inflation aside, there is a key anomaly in US data: while the country’s economy is apparently going gangbusters, jobs growth is increasingly weak. The weaker jobs data is currently giving the Federal Reserve cover to cut rates, but could that store up inflationary problems if weaker jobs is not necessarily a sign of weaker economic growth? Why might that be so? AI, of course.

The big promise of AI is that it can deliver productivity benefits for companies – or, to put it another way, replace costly humans with far less troublesome tech. While AI true believers insist new employment opportunities will emerge, they have yet to do so. As such, a situation where economic growth is increasing and jobs decreasing is plausible.

For the time being, however, any link remains unproven. “Anecdotal evidence suggests jobs are already being lost in sectors vulnerable to AI automation,” notes the team at Oxford Economics. “Overall, though, firms do not appear to be replacing workers with AI on a significant scale and we doubt that unemployment rates will be pushed up heavily by AI over the next few years.”

And they continue: “While a rising number of firms are pinning job losses on AI, other more traditional drivers of job lay-offs are far more commonly cited. What is more, we suspect some firms are trying to dress up lay-offs as a ‘good news’ story rather than bad news, such as past over-hiring.” The group points out that even in areas of notable weakness, such as graduate unemployment, there may be other reasons for the slowdown. As always, correlation does not mean causation.

Nevertheless, it does liven the debate on just who wins from AI. The assumption for much of 2025 has been that it will be the hyperscalers yet that view is being increasingly challenged. China is building a competitive AI ecosystem, while much of the semiconductor supply chain is located in Taiwan and Korea. That suggests emerging market companies could be greater beneficiaries in the year ahead.

“It is perfectly reasonable to be positive on AI’s prospects without adhering to the perceived wisdom the companies leading the charge today have sustainable valuations,” observes James Klempster, deputy head of multi-asset investment at Liontrust. “The Magnificent Seven are priced very richly on once-in-a-generation levels of profitability; a heady mix that, through the lens of history, we see typically does not end well for investors.”

3. Diversification – a cure for what ails US?

The current US administration has made unpredictability its calling card – or, as John Chatfeild Roberts, manager on the independent funds/Merlin team at Jupiter, puts it: “Diplomacy is not in the Trumpian lexicon; a spade is not a shovel, it is unequivocally a spade. He is insensitive to collateral damage and largely impervious to views that are not his own.”

There is a chance that investors start to tire of this unpredictability over 2026. At the margins, the administration has started to meddle in the workings of corporate America – whether it is pushing US oil companies to invest in Venezuela or interfering on who companies should employ or where they can trade. Add in extensive tariffs and a weaker dollar and global investors may start to balk at the price they are paying for ‘US exceptionalism’.

This had already started to happen in 2025, with a narrowing of valuations between the US and elsewhere, but Klempster believes there is further to run. “While markets other than the US have moved from ‘cheap’ levels, they are not expensive,” he says. “We believe they are at levels that justify allocations that are greater than would be attained through a naïve market-capitalisation approach.”

One caveat here would be that, should the mid-terms go against the Republicans, Trump could be defanged. It is possible that investors will be reassured by a lame duck in the White House, who cannot start new wars or impose new tariffs – which in turn might serve to improve the outlook for US stockmarkets.

4. The rise and rise of emerging markets

While the globe’s developed nations adjust to a new world order, many emerging markets are making hay. China has emerged from its trade war with the US with barely a scratch, having strategically reduced its dependence on US markets in anticipation of a second Trump presidency.

“Emerging markets absorbed the tariff shock surprisingly well,” says Robert Gilhooly, senior emerging markets economist at Aberdeen. “China, often the focal point of US trade actions, largely shrugged off the impact. Policymakers redirected exports and maintained growth momentum by ramping up green investment.”

Other emerging markets benefited from a confluence of supportive factors, he adds, with the roll-out of AI technologies in the US boosting global demand for components and services; a weaker dollar easing financial pressures, enabling many central banks to cut rates; and “Washington’s eventual retreat from its most aggressive tariff threats” helping calm investor nerves. According to Trustnet data, the average fund in the IA Global Emerging Markets sector rose 21% over calendar-year 2025.

This strength could continue into 2026 while the relative risks of emerging markets versus their developed counterparts may be dissipating, as US policymaking grows increasingly erratic. Certainly, that would appear the conclusion of bond markets, where spreads for emerging market debt over US debt have been narrowing.

For his part, Gilhooly expects that downward pressure on the US dollar to continue. “Disinflationary pressure from excess capacity in Chinese manufacturing can help moderate prices further,” he argues. “Tighter government budgets will also play a role. All of which should reduce the barriers for emerging market central banks to cut policy rates.

“President Trump’s return has tested emerging markets – from policy decisions to tariffs. Nonetheless, many nations have not only survived his comeback but thrived. Several are in strong fiscal positions and have recalibrated their trading partnerships following Trump 1.0.”

At the same time, data from Capital Group shows emerging markets are forecast to have the strongest earnings growth across the world over 2026 – at 17.1%. By comparison, US companies come in at just above 14% and Europe slightly above 11%.

5. European solidarity

Sclerotic policymakers in Europe are facing some major challenges. With US backing for Ukraine waning, and potential threats to Greenland in the mix, Europe needs to shore up its defences. It also needs to confront its reliance on the US technology sector and start to ensure it can thrive should its former friend turn cold.

“Europe is adrift in a global tidal race dominated by the United States and China,” is how Jupiter’s Chatfeild-Roberts sums up the problem. “The leaderships in both Washington and Beijing largely deride their European counterparts. Contempt [ whether undisguised or thinly veiled – oozes from both.”

Will Europe get its act together? Perhaps more importantly, will it act as a bulwark to the superpowers on either side and help preserve some vestige of normality in the global economic order? The continent should not be toothless, given its economic power, but it has yet to come up with a coherent response.

Overwhelmingly, the message for the year ahead is more noise. Investors will need to be prepared to look through a US administration that has made disruption its selling point. It has started with Venezuela, the question of where it will end is open-ended.