“So the company’s CFO, who we think should be sacked immediately …” Vishal Bhatia, senior fund manager on the £415m JOHCM UK Dynamic fund, pauses and looks in my direction. “Just to be clear,” I offer, “I am quite good at knowing what is ‘off the record’ in these meetings.” Bhatia seems reassured – or at least he carries on talking about … well, as I say, I am quite good at knowing what is ‘off the record’ in these meetings.

And ‘these meetings’, just so you know, are the result of a conversation I had with fund research pioneer Peter Toogood as Wealthwise was coming into being this time last year. He was CIO of what was then The Adviser Centre, part of the Lloyds-owned Embark Group but, since October last year, is now independently owned and rebadged as Fund Research Centre, where Toogood is now managing director, investment.

The plan is that, from time to time I am invited to sit – quietly – in on a meeting where analysts from the company quiz the team behind one of their featured funds. In this instance, the line-up is the aforementioned Bhatia and co-fund manager Tom Matthews, accompanied by JO Hambro Capital Management sales director, strategic partnerships, James Allcorn-Austen.

One benefit of this arrangement is that Toogood and his colleagues – here, senior research analyst Marianne Weller and research analyst Freddie Thompson – tend to ask more informed questions than I do. Another, as I mentioned in our first Fly on the Wall piece – on Artemis US Smaller Companies – is the result is not the one-off chat journalists tend to have with fund managers and more the latest exchange in an ongoing conversation.

Possible downsides, meanwhile, are the need to ensure my presence does not act as a drag on what the managers feel they can say – now hopefully addressed with Bhatia – and the fact I have zero control over where the conversation goes. While my inclination towards discretion has always made me a pretty lousy news reporter, I like to believe my ability clearly to convey a fund manager’s thinking tends to save me as a features writer.

Genuine insights

This gig, however, is a test. It feels like every time one of the fund managers works up a head of steam – very handy for a smoothly-flowing article – the Fund Research Centre team interrupts them with another question. Embarrassingly, it takes a while for it to dawn on me this is likely deliberate – some genuine insights into a fund coming when its managers are edged away from the home-turf comfort of spreadsheet and slide presentation.

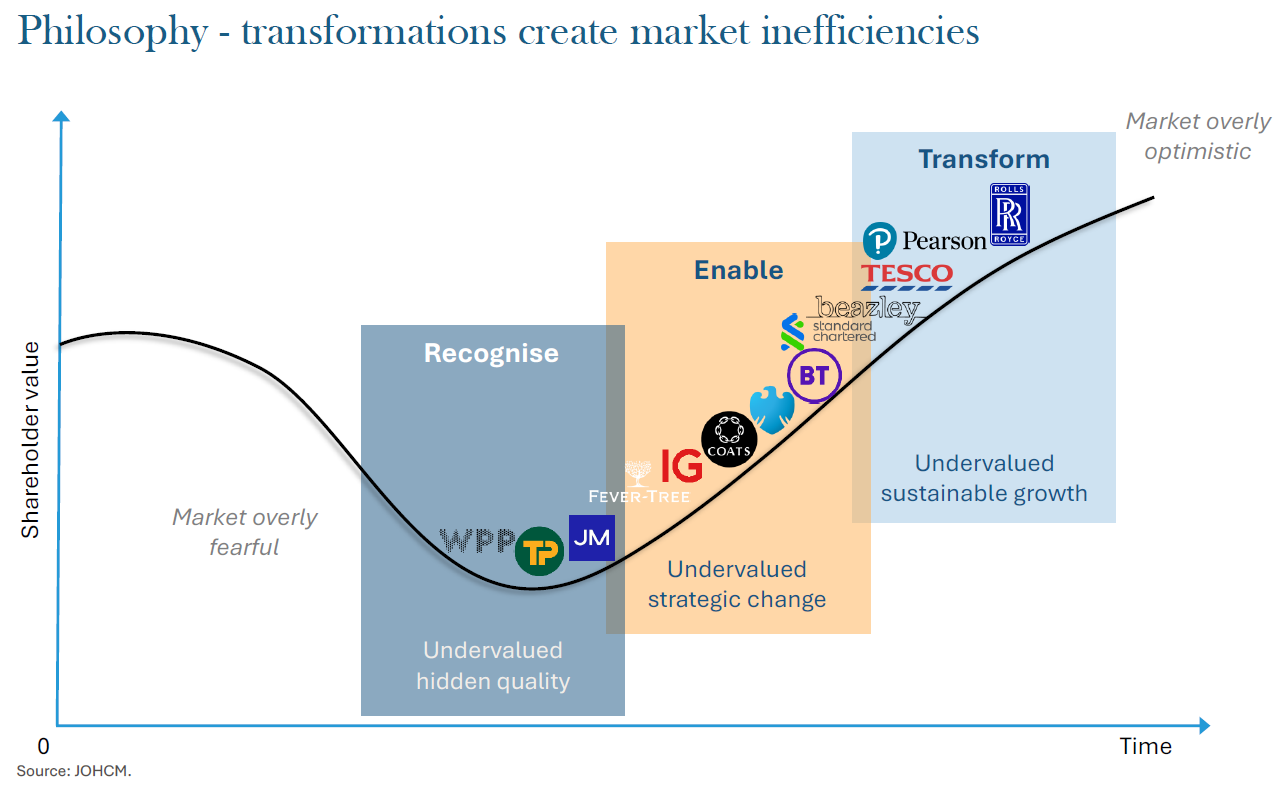

Either way, though, Toogood throws me a bone by asking Bhatia and Matthews about the fund’s philosophy and current portfolio positioning – with the unspoken element being previous manager Alex Savvides’s departure for Jupiter in 2024. “We are always looking for differentials,” Toogood adds. “Three years ago, value in the UK was everything but now that is not quite the case – so where do you think you have added something different?”

“We are looking for quality businesses with a proven track record and, better still, management teams with a proven track record of generating recurring equity value.

Peter Toogood, Fund Research Centre

Vishal Bhatia, JOHCM

Matthews takes the question on, replying: “UK Dynamic only focuses on business transformations – because that is where we see recurring market inefficiency. As we all know, markets are predominantly very linear but change situations are non-linear – and, in a world of more and more ETFs and basket trades, we actually think market efficiency continues to exist. People are more short-termist than ever and are just not doing the work.

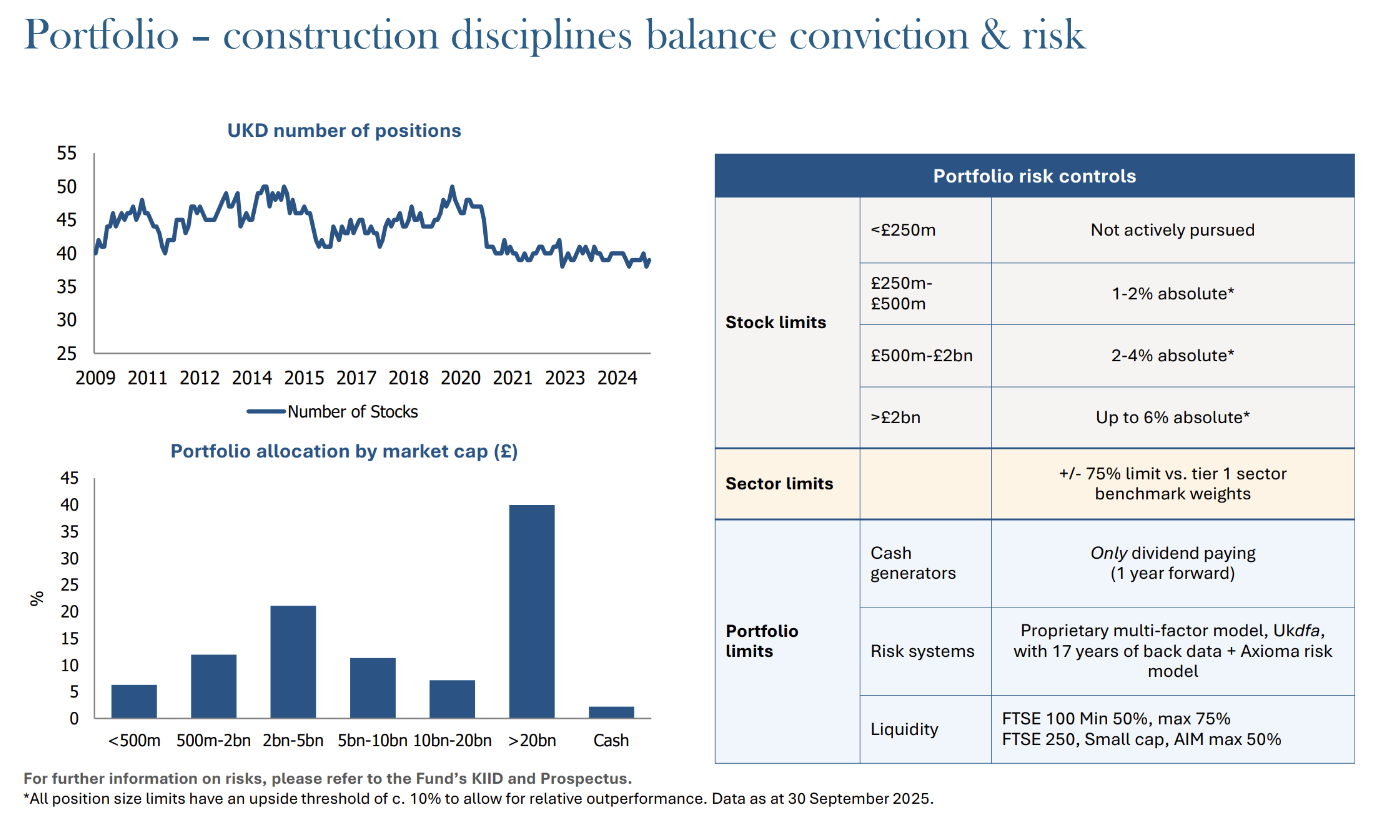

“That said, we are not looking for just any kind of turnaround – this is not a recovery fund. We are looking for quality businesses with a proven track record and, better still, management teams with a proven track record of generating recurring equity value. The portfolio construction has been the same discipline since the fund’s inception in 2008 – in fact, Vishal set up the disciplines with Alex back in 2008.

“We have disciplines around the sectors, around position sizes and, particularly, around the cashflows. As an example, we will never buy a company that is not going to pay a dividend within 24 months – in effect, we will give it a year’s grace – and that is to avoid the most distressed and over-levered situations, which you can see a lot of with transformations.”

Institutional-grade systems

The final differentiator Matthews flags is the “institutional-grade systems” developed and used by the team. “We have proprietary approaches to how we calculate our valuations and manage our risk,” he elaborates. “We do all our own models, which means we can compare apples with apples when it comes to the actual valuations and the allocation of capital but, importantly, when we think about debt and leverage in those businesses too.

“We use a repeatable process for all our models, including our proprietary ‘UKdfa’ multi-factor risk-rating tool, which Vish built with Alex back in 2008. That is a way we bring external data into how we manage our portfolio and our ideas – as well as challenging our own conviction on stocks.” On which note, Matthews looks to draw our attention to two slides – although that turns out to be optimistic.

He does manage the first one – set out below – which encapsulates the team’s take on business-transformation cycles. “What we are looking for is quality businesses that have started to believe their own hype a little bit,” Matthews explains. “They start to build an empire rather than equity value – taking on too much leverage, say, or making an acquisition that is outside their wheelhouse in terms of strategy.

“That stretches them into riskier areas and starts to erode returns – and you can see businesses unwind. They lose the confidence of their staff and, importantly, their shareholders and the share price falls over – but then, internally, people recognise something needs to change. That is the signal we are looking for. Often it will be a change of chair, a change of CEO, a change of CFO, a change of strategy – in the best cases, it is all of those.

“That is when that market inefficiency I mentioned starts to come into play because what you are seeing there is that non-linear change – and where we can, in the first instance, see valuation margin of safety. As that transformation starts to take hold, though – as the new strategy is being enabled – the market will be slow to pick up on it because it is not as close to how much has changed.

“That is the second phase and then, finally, you get through to the transformation, which is where businesses have been through that process, they are coming out the other side and they are even better than their previous successful selves. Often they are creating new markets or displacing the previous leaders in existing ones – and those are the businesses we can hold all the way through.”

Before Matthews can move on to his second slide, however, two questions come his way in quick succession – Weller raising the managers’ ‘sell’ discipline in the context of top-10 holding Roll-Royce; Toogood name-checking WPP, another holding, as a “potential AI loser” and, more broadly, to interrogate whether the rate of transformation has increased and thus made the fund’s investment philosophy more challenging in recent years.

The joy of accounting

As Bhatia clicks his mouse and fills a large screen on the wall with numbers, you sense this is the moment he has been waiting for. “You are asking questions about two different companies but let’s try and help bring the process to life,” he says. “The fact is, when we talk about having a consistent process, you have to know your stocks inside-out.

“What we are looking at here is our WPP model, where you can actually start to see how we think about the business’s different divisions and its P&L, all the way down to our view on its EPS numbers.” I nod along and try and look as if balance-sheet analysis is all part of my working week while, in contrast, Toogood gives the impression it is actually his idea of a fun night-out, adding: “This is why I came along today!”

Bhatia seems of a similar mind. “When I joined the industry, the guy I learned a lot from gave me an intentionally unbalanced balance sheet and told me to balance it,” he says. “That was my first task and I loved it because I learned so much.” “I have no idea why all fund managers are not obliged to be accountants,” observes Toogood.

“Well, that is a discussion we should have,” agrees Bhatia. Though not today, as he continues: “The point is, we have the P&L and a long-term DCF – and obviously that will feed into your cash conversion and free cashflow yields and so on. This is the bottom-down version on my balance sheet – but then we should not live in our own world. We should know where our numbers are versus consensus.

“Now, why is all of that important? Purely because, in the industry we live in, a lot of things are happening way too fast. And you are absolutely spot-on that everyone believes WPP is an ‘AI loser’ – that is a given. Yet what we are looking for from companies like WPP is very simple: can we see a free cashflow inflection? And we think this business is on the cusp of a free cashflow inflection, going from £400m to £1.2bn.

By the numbers

“Importantly, these are our own numbers and they are not based on any aggressive assumptions on factors such as market share – plus, we also believe WPP offers the element of hidden assets. As everyone knows, WPP’s Kantar shareholding is potentially up for sale, which could allow for the parent to be de-leveraged – but I also think the business could probably go a bit further and lose one of its prized assets to refocus its energies.

“As for Rolls-Royce, I would say it is ‘middle of the pack’. Remember, all these stocks are rated against each other in our portfolio – in other words, to be included, they are fighting against all our other holdings. Now, the pushback you get on Rolls-Royce is, Look at the share-price charts – but our model will tell you it will be generating £7bn of free cashflow per annum and the enterprise value is only £90bn.

“As Tom said, we get conviction when we see free cashflow inflection. Effectively, if you start giving it a fair multiple, there is significant upside in Rolls-Royce without any balance-sheet risk or any earnings risk – at this point in time – but we still have the optionalities of SMRs [small modular reactors] and narrowbodies [aircraft engines]. Whether they take market share or not remains to be seen – but clearly that is a 2035 story.”

Tom Matthews, JOHCM

Marianne Weller, Fund Research Centre

Here Weller pivots the discussion to how active the team has been on its weighting of Roll-Royce – prompting Bhatia to observe: “You have to take away the market noise and you can only do that by position size” – before Toogood changes tack once more, asking: “Can you give an example from the last 12 months of when you do meet a valuation and it is time to say goodbye to a stock?”

“That is a good one and an example would be Elementis,” replies Matthews, reaching for his slides. “What you will get an idea for is, we are not just looking for valuation, we are looking for levers as well – and the four we look at are operational turnaround, hidden assets, changing market dynamics and balance-sheet deleveraging. The best ideas in the portfolio have at least two of those – normally three of those – and …”

Identifying hidden assets

“Sorry to interrupt again but how often do you really find hidden assets?” asks Toogood. Matthews immediately offers Johnson Matthey, while Bhatia points out nobody cared about SMRs when the fund owned Rolls-Royce in 2019. “OK – but how many have you found in, say, the last five years?” Toogood presses. “You can see where I am coming from.” “And are they concentrated in a specific sector – say, pharma or oils?” adds Weller.

“I would say the portfolio has hidden assets of maybe 15% or 20%,” replies Matthews. “And, as for sectors, I would probably say industrials. Only this morning, for instance, we had Johnson Matthey talk about Clean Air. That is the old catalyst part of its business – but it is now talking about using that technology to monitor the emissions out of data-centres. Nobody even used to talk about that yet now it has a multi-year contract.

“I suppose it comes down to your definition of ‘hidden asset’,” acknowledges Weller and Toogood adds: “Like a hidden asset that can be used to pay down debt. Fair enough.” “PZ Cussons has all these factories that were not being utilised because the previous ownership had a questionable record of capital allocation,” notes Bhatia “So suddenly they are saying, We have found £30m of assets, which we will monetise to reduce our debt levels.

“As engaged shareholders, Tom and I were always saying, Focus on your gross debt – get that down and sell your assets. So what do they do now? They sell the Nigerian palm oil JV – and there are more assets they are selling in Thailand and Indonesia. This is hidden assets, this is de-gearing – but the market does not recognise it as such because everyone is myopically focused on earnings numbers.”

Increased rigour

Time for another swift switch of focus – and you do feel it was only a matter of time before Toogood got around to asking this question. “And to what extent are you doing things differently from when Alex and you were working together?” he says, before adding: “We are looking for differences so it is fine – you are allowed to express them!”

“Philosophically, UK Dynamic was always trying to do these sorts of things,” replies Matthews. “We were always looking for ‘value unlock’ but it was never this rigorous. Now it is: I need to go through the valuation. I need to know I have my margin of safety. I need to know this is not just a cheap stock and that it also has levers we can pull.”

“We drive conviction by ensuring we have a very consistent bottom-up framework,” adds Bhatia. “Alex likes his models but every model and every level of detail is very different. We have now built this consistency and modelling framework across a number of companies – and our analyst Utkarsh Katyaayun, who joined us in 2021, hit the ground running. He himself has taken our data bank of models from 50 or 60 up to 70 or 80.

“And when Tom rejoined the team, he said, We are getting this into the live environment. We need to ‘industrialise’ this whole process to bring transparency – and we are going to make our internal debating process consistent. So I recently had the best holiday ever – during it, seven mega-caps all reported on the same day and Tom and Utkarsh made all the right calls because the process is so systematic and therefore consistent.”

Capitalisation piece

Toogood nods and moves on to discuss the team’s willingness currently to allocate more to smaller and medium-sized companies than their peers. “I thought the capitalisation piece in your presentation [shown below] was really interesting,” he says. “There seems to be no particular desire among your peers to drive down past – let’s call it 15%, all in. You appear to be to be more expressive, however, so could we talk to that for a bit?”

“We are now at a four-year high for our midcap exposure and, to be honest – alongside the levers for change and transformation stories we mentioned – we have been led there by valuations,” says Matthews. “What we have found fascinating is, while we can all maybe understand why UK domestics are being hit over the head, that is dragging down the broader indices around them as well.

“So where we are finding the interesting opportunities is with international assets, such as Fever-Tree – businesses that are market-leading, globally, in their products but maybe it is a complicated situation. As an example, the Molson-Coors deal that is going on with Fever-Tree is making it slightly opaque about where the cashflows are today – but it is quite obvious when you look far out.”

Given the liquidity constraints associated with the small and midcap space, Weller asks how the managers think about sizing and positioning, adding: “I am thinking about a very specific stock from many years ago –Restaurant Group.” “We all know what happened in 2020 to this fund,” acknowledges Matthews (although, at least as far as one person in the room is concerned, he is being way too generous).

Off-balance-sheet debt

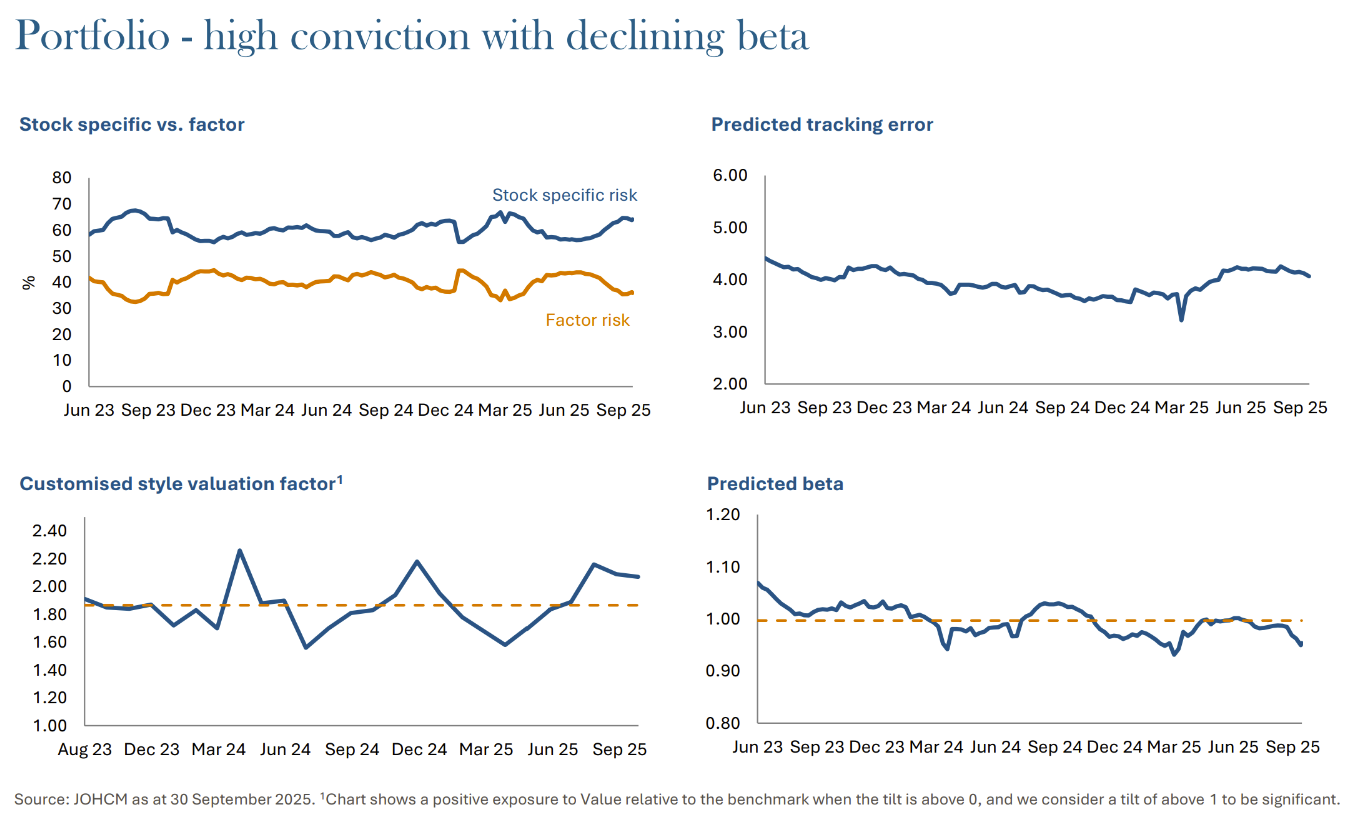

“We told the market at the time it was around factor concentration or factor risk – and that was correct. What is really interesting, however, is if you look at our DfA balance-sheet risk metric, you can see what was actually happening was we had taken on too much debt going into the end of 2019. And what was that? It was a lot of off-balance-sheet debt.”

“The realisation Tom and I had is, as equity investors, we are right at the bottom of the capital stack to get paid,” adds Bhatia. “So do we want to gear ourselves up unnecessarily? Absolutely not. What we like to see is new managers coming in and backing the equity structure. And, if you want to gear up, then you need to tell us how you will de-gear to make sure we are not taking unnecessary risks. In the UK market, you just do not need to.”

Toogood seems happy to stay with risk for the time being, saying: “I used to ask managers, Did all your stocks go up or down yesterday? And they would look at me and go, What question are you really asking? And it comes down to, How do you think about the risk in the portfolio? So many managers respond with a risk system but then we go, What does that mean?

“To put it another way, Diageo does not work in the same way as Rolls-Royce or Smith & Nephew. So do you believe you have embedded that in the way you build your portfolios? I know it is the factor-risk question again – but the number of times you used to catch managers out. They would have a high information ratio after, say, 1998/99 and we would go, Of course, you do – you have 60% in tech stocks. So how do you think about that?”

Matthews just so happens to have a slide for that. Pointing to what you see below, he says: “Obviously we are bottom-up stockpickers but we do spend a lot of time checking that, ultimately, the portfolio as a whole makes sense too. We get this data from our risk team and put it into our dashboard and, as you can see in the top-left corner, what you are looking to do is make sure your stock-specific risk is around 60% – that is a good level.

“What is most impressive though, I think, is the bottom-right chart, which shows our predicted beta has gone down. As Vish was saying, we felt the way this portfolio generates returns is through that idiosyncratic unlock of value – through the levers we were talking about. We don’t need to then take beta and we don’t need to then take leverage on top of that – let’s just find the great stories and back those.”

The looming end of the meeting prompts a flurry of questions. On trimming back the fund’s Land Securities position, Matthews says: “It was not so much the balance sheet being overgeared as the optionality around the balance sheet – there wasn’t any, as far as we could see. Plus, we already held Shaftesbury – so the Mayfair of shopping, at the same discount to book and selling some of its assets at book – which was far more interesting.

“So the question became, What was the Land Securities position doing for us? OK, maybe it was giving us insurance against bond yields coming lower but what we worked out was, Actually, why don’t we buy some assets that have longer duration – the Fever-Trees and so forth, the growth assets – so we could find a much better way of generating returns for investors through that?”

And the pair’s take on the healthcare sector, which they are playing through a maximum overweight position in GSK? “We saw it as a platform business priced as a single-product company, which is exactly what happened,” explains Bhatia. “We model all the drugs so it is a properly detailed picture.” “A lot of investors will argue that, since they do not understand all the drugs, they cannot make a suitable model,” Weller points out.

“We may not understand individual drugs,” Matthews concedes, “but you can make assumptions across the board. Companies will, for example, give you peak-sales expectations – which you can layer against a ‘normal’ drug – as well guidance out to 2030. With those sort of indications, when you do the bottom-up and comparative top-down guidance, you can see where there is a large margin of safety in terms of consensus versus guidance.”

“Last question, then,” nods Toogood. “What has been happening on the flows front?” “There is lots of interest,” says Matthews. “We have won three new clients over the last three months while one big win was our largest client adding more money, having initially halved their usual position.” Or, as Bhatia observes: “We have clearly seen a stabilisation.”

‘Let the ball come to you’

At one point in the conversation, Bhatia highlights the fund’s cash position – which usually sits between 2% and 4% – as an interesting indicator investors should watch. “More recently, our cash position has come off from 3.5% to about 1.6% – which is still healthy – but it just tells you something about the fight for capital,” he says. “As you know, if you are not having that fight for capital, you will naturally see your cash position rise a bit.

“While others may be finding that at the present time, however, we have been fighting for capital because a number of the ideas we like are really demanding more. So, to your point about how we keep ourselves real from a risk-position perspective, clients can see our cash position and conclude we have numerous ideas because it is low. And that is true – we do.

“Now, we are not focused on the cash position – this is the end-result – but it gives you the clarity of how we are thinking because we can move when we want to. If things change, we don’t mind going up to 4% tomorrow – because that is the range we give ourselves. Still, it has to be driven by bottom-up, not top-down, considerations – and we know the ideas will come to us.

“I love my cricket and you never grab when catching the ball – you let it come to you and the catch will come.” “I avoid sports where the ball comes at you,” Toogood interjects. “It is why I play golf – I get to do the hitting!” “Well, investing is exactly like cricket in this respect,” Bhatia assures him. “The idea will come but, if you snatch at it, you will make mistakes.”