The case for the Japanese equity market and its latent value is not new – but what is new is the convergence of multiple catalysts for this value to be unlocked. While investors should be cautious about the risks that temper the opportunities, on balance conditions in Japan today appear uniquely positive for supporting strong equity-market returns in 2026.

The arrival of new prime minister Sanae Takaichi, which we analysed here back in October, is clearly the most material change to affect the market and its outlook – but, crucially, this development is additive to several other positive developments in recent years. Even in the context of 2025’s success, the combination of the following four factors could make 2026 an extremely strong year for the Japanese market.

1. Policy reforms of the Takaichi regime

Under Shinzo Abe, the Japanese economy made undoubted progress. The election of his protégé, Sanae Takaichi has therefore come with very high expectations. While this might suggest she and her team will find it difficult to live up to their billing, so far this has emphatically not been the case.

The policy reforms announced so far amount to a fundamental reorientation of the fiscal stance of the Japanese government and our own forecast is that her agenda represents the ultimate catalyst for the Japanese market to go on to hit new all-time highs in 2026.

Importantly, Takaichi and her cabinet are starting the new year with very high approval ratings, with various polls putting her and her team on 70%-plus approval ratings. This means she has the legitimacy and popular support to get her agenda moving quickly.

The Japanese cabinet has already approved the first economic stimulus package – valued at approximately ¥21.3tn (£100bn) – and a great deal more is expected to follow. Other welcome policy initiatives are focused on moderating the rate of price increases; and launching a programme of national renewal centred on upgrading infrastructure, channelling investment into strategic technologies and rebuilding defence capabilities.

A key risk with this agenda is that inflation spikes – but our current modelling projects inflation to hold steady at around 2% in 2026. If this delicate balancing act between spending and inflation can be accomplished, then monetary and fiscal policy will both have room to support growth and rising earnings for Japanese corporates.

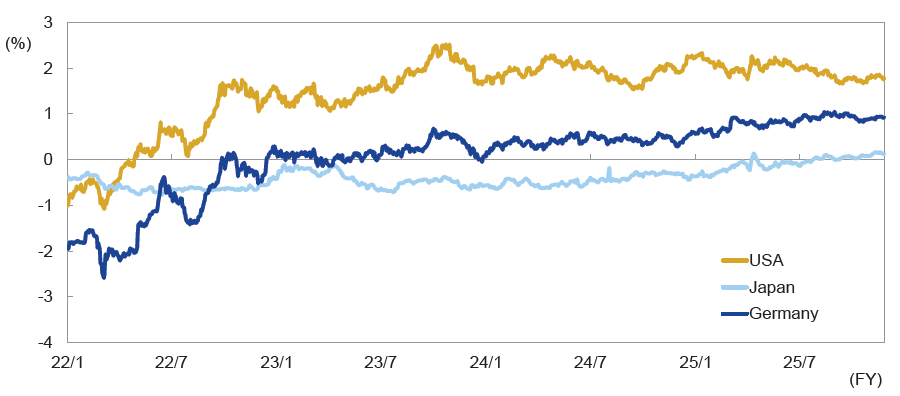

As the following chart highlights, despite the rise in yields recently, real 10-year government bond yields in Japan are still noticeably below those of other western governments and, in fact, have only just re-emerged into positive territory. As such, our view is that Japan’s fiscal situation is stable enough to provide room for fiscal stimulus without endangering debt sustainability.

Comparison of 10-year real government bond yield

“Takaichi’s arrival on the Japanese political scene may be seen as the latest piece of the puzzle to fall into place – and the image now revealed is one of an economy with tremendous residual strengths and the latent potential of a coiled spring.

Note: Data is from 03/01/22 to 28/11/25. Source: Bloomberg

This extreme willingness to put the fiscal firepower of the state to work reinvigorating the economy makes Takaichi’s regime stand out from her predecessors and means ‘this time really is different’ to past muted revivals of the Japanese market. Her arrival on the Japanese political scene may be seen as the latest piece of the puzzle to fall into place – and the image now revealed is one of an economy with tremendous residual strengths and the latent potential of a coiled spring.

2. Monetary normalisation

Importantly, unlike her predecessors who may have wanted to commence proactive fiscal policy but were unable to do so due to the absence of suitable conditions, Takaichi has entered office with a supremely supportive backdrop.

Our own economists see the Japanese economy as now firmly rooted on a path towards what we term as ‘1, 2, 3 normalisation’, by which we mean 3% wage increases taking place in parallel with 2% price inflation and 1% productivity growth.

The conjunction of these three indicators symbolises the ideal macroeconomic environment for Japan to continue to grow in 2026 and, when achieved, would signify the normalisation process has been essentially completed.

Picks for ‘26 – read more

Artificial intelligence: Stuart Gray, WTW – Potential v FOMO – the two sides of the AI coin

Chinese equities: Mike Willans, Keyridge – Ride the wave of reform and innovation in China

Global growth: Daniel Murray, EFG Bank – Global risks and opportunities for the year ahead

Healthcare: James Douglas, Polar Capital – Is healthcare the smart complement to tech?

Japanese equities: Sumitomo Mitsui DS AM – Four catalysts for Japanese equities in the year ahead

Luxury brands: Sean Koung Sun, Thornburg IM – Scarcity is engine of long-term value creation

US smallcaps: Bill Hench, First Eagle Investments – US smallcaps look poised for a comeback

3. Return of inflation

Not unconnectedly, inflation has returned to the Japanese economy, which has now seen more than three years of consecutive monthly price rises. The rekindling of some moderate upwards price pressure is a welcome development for several reasons.

First, during the deflationary decades, consumers responded to falling prices by withholding or postponing purchases. This progressively sucked demand out of the market, leaving Japanese companies without the tailwinds provided by domestic consumer demand their foreign competitors could harness.

Second, the lack of inflation meant the time-value of money created perverse incentives. With prices gently falling, the purchasing power of a single unit of currency effectively rose over time, thereby creating a powerful incentive to save rather than spend, again choking off the demand businesses need to see before they will invest.

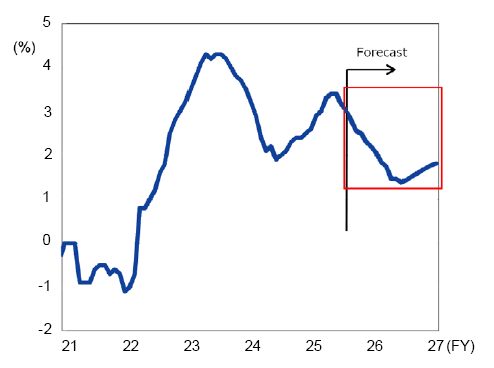

The relative improvement in Japanese Consumer Price Index (CPI) over the past few years is shown in the following chart – and our expectation is it will settle in early 2026 at the 2% level. Crucially, although the depreciation of the yen caused by comparatively low rates has meant import prices have risen, the major cause of the uptick in inflation appears to have been rising wages.

Bank of Japan’s core CPI forecast (year-on-year, %)

Note: Data is from January 2021 to March 2027. BOJ’s Core CPI is excluding fresh foods & energy. Data from April 2025 is forecasts. Source: Bank of Japan

This is positive for the macroeconomic outlook as it means the long-awaited virtuous cycle of higher wages feeding into higher prices driving corporate earnings growth – which in turn means employers can accommodate higher wage demands from staff – is beginning to become anchored in firms and consumers’ expectations about the future.

We should acknowledge, however, that Japan’s inflation rate over recent years has been disproportionately driven by food costs, which are largely imported. As such, if trade disruptions persist, then inflation could settle at a higher rate.

That said, we are currently optimistic about the prospects of Japan’s trading situation avoiding further deterioration. If this thesis is correct, the return of inflation means investors can expect Japan to follow a ‘normal’ pattern of development again – and, crucially, one that is highly supportive of rising equity valuations in 2026 and beyond.

4. Governance reforms

Having begun over a decade ago, these reforms are by now in one sense ‘old news’ so investors might be wary about accepting the validity of the claim they are now moving the needle.

Nevertheless, the gradual but consistent accumulation of momentum for the reform agenda has today created a genuinely dynamic context in which Japanese companies are not only open to the prospect of change but are actively pursuing it. This is yet another way in which all the groundwork for the success of Takaichi’s regime is already in place.

The five key measures of the corporate governance reform agenda are:

* Listing and delisting trends: This is to ensure only viable enterprises that act as responsible stewards of capital are admitted to the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE). While the comparatively high number of listed entities is a boon to active managers, the stricter listing requirements are aimed at reducing the number of particularly smallcap stocks that list simply due to the prestige still associated with being a public company in Japan. In fact, delists are set to rise markedly as companies who have failed to create shareholder value leave the market.

* Expanded disclosure requirements: The TSE is further requiring all companies to publish their plans to improve capital efficiency. This allows investors to gain a much higher degree of transparency over what investment plans a company has, allowing greater discretion over where to place their capital. Although the headline emphasis has consistently been placed on raising price-to-book ratios over 1x, in fact the focus is much broader and geared towards incentivising overall improvements in capital efficiency.

* Changing attitudes to shareholder activism: Related to the two measures above, the traditional disapproval towards activist shareholders has noticeably changed in the past few years. This has sparked a chain reaction in Japan whereby all shareholders have come to expect their voice to be heard by management, with overall positive results in terms of how accountable managers are. Both the presence of activist funds and the quantity of proposals they are putting forward have risen dramatically in the past few years.

* Utilising excess cash: While many stakeholders can be agnostic as to precisely what cash is deployed to do, there is a widespread consensus it does need to be put to work in some manner. This could be through share buybacks, raising dividends, capital investment and perhaps even simply higher wages feeding into the general narrative of the virtuous cycle of rekindling inflation.

* Independent directors and boardroom diversity: Long established as the norm in other developed markets, another key plank of the reform agenda is the rise in independent directors on boards. Now enshrined in Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, this stipulates companies listed on the Prime Market should appoint at least one-third of their directors as independents, while companies listed on other market segments should appoint at least two independent directors. The impetus this gives for company management to act as responsible stewards of shareholder capital was initially resisted but has become increasingly accepted as the years have gone by.

Ultimately, our core thesis is the Japanese equity market re-rates to a higher valuation multiple in 2026, driven by multiple catalysts outlined above – most centrally the reform agenda of the new prime minister.

This should result in a narrowing but not full closing of the valuation gap with the US and other developed markets and will see the Japanese market achieving new all-time highs.

While downside risks around trade tensions, the inflationary path and heightened risk of policy failure may create some short-term volatility, on balance we see significantly more upside potential and opportunities than risks for 2026.

This is an edited version of a white paper by analysts at Sumitomo Mitsui DS Asset Management, one of the largest investment management companies in Japan