If, on 1 January this year, you were blessed with a perfect view of all the challenges investors would face in 2025, could you then have offered a similarly accurate market forecast? This is the question Hugh Gimber, global market strategist at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, poses to the audience of Wealthwise’s Autumn Wealth Forum earlier this month – before suggesting everyone would have been well wide of the mark.

“Had you listed all of the trade news, all of the geopolitical issues, all of the UK’s many challenges and so forth and then said equity markets would be up 15% while bond yields would be a long way down in the US and holding pretty well elsewhere in the world, those two things would have felt completely incongruous at the time,” he reasons. “And yet, here we are.”

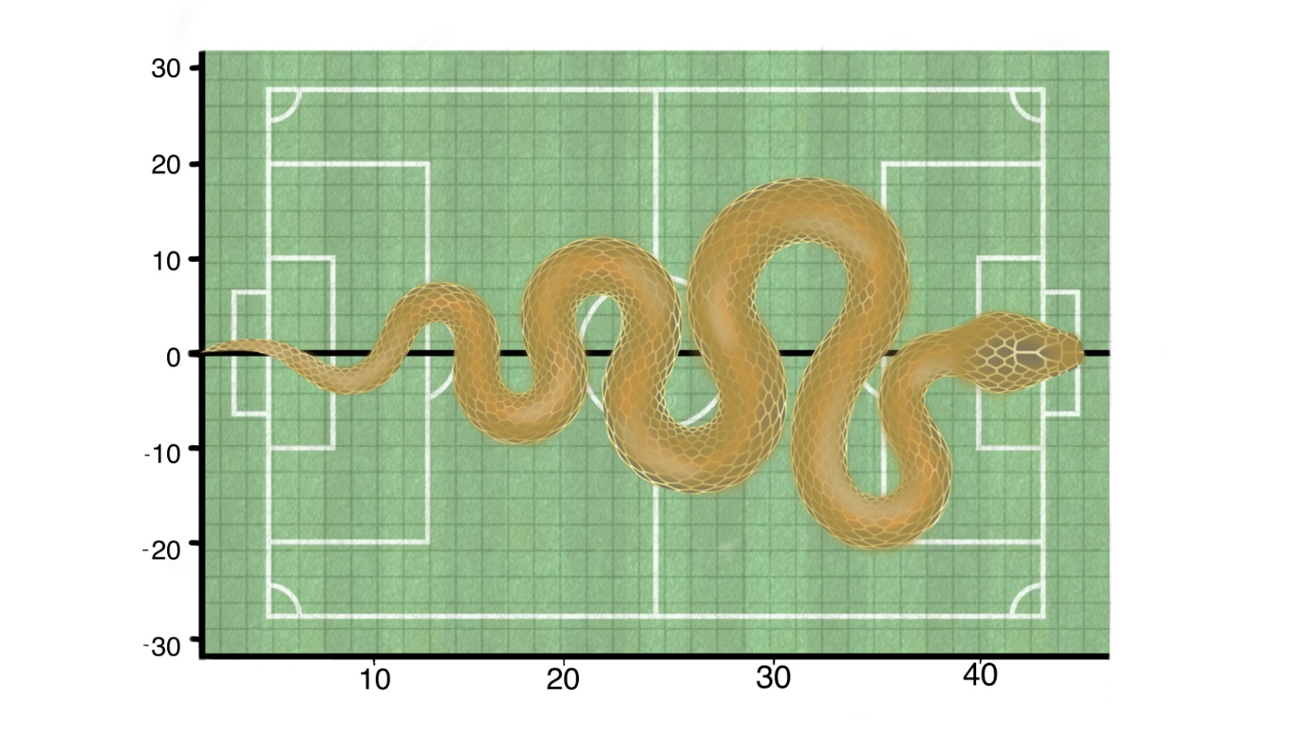

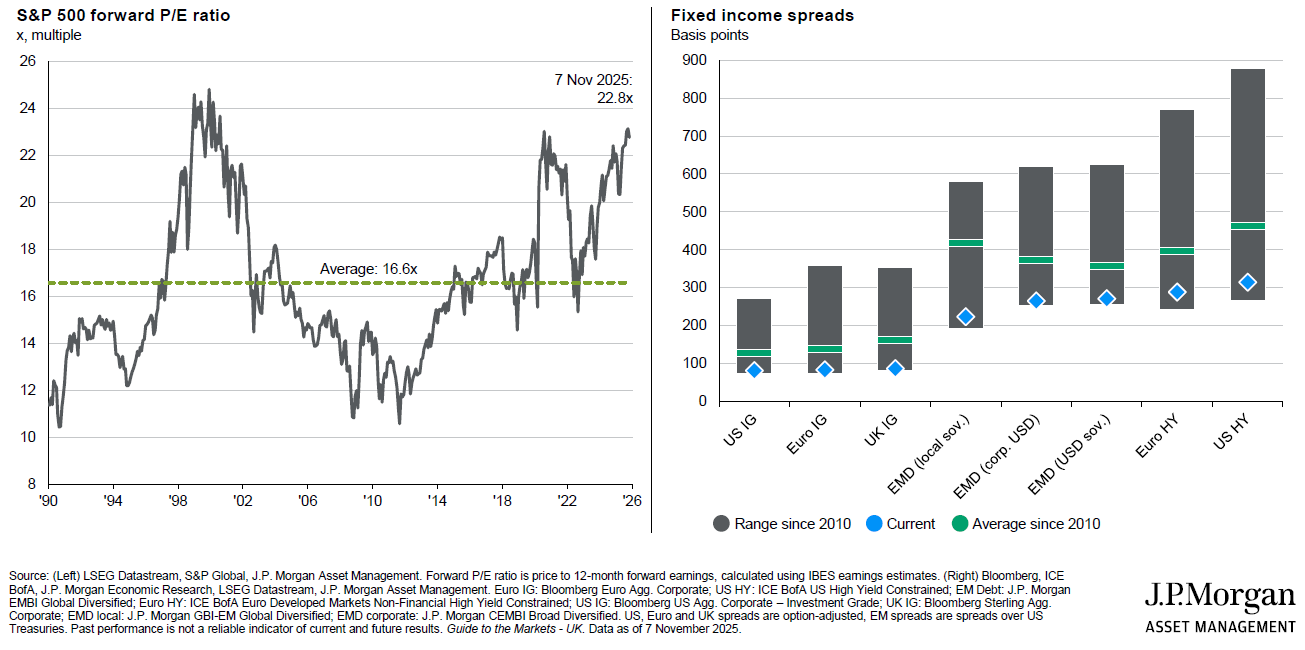

As Gimber puts it, pointing to the following slide, markets are “about as happy as they come” with, for example – and despite the volatility prompted by ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcements in early April – the US stockmarket thus far enjoying no fewer than 36 all-time highs over 2025. As the righthand chart shows, meanwhile, credit spreads are largely at record levels, whichever market you pick.

Happy markets

“For the Fed – provided the labour market remains on this cooling path – sub-4% inflation is probably good enough but it is one of the key issues we need to track next year.

“So markets are telling you this geopolitical noise is exactly that – purely noise,” says Gimber. “There is nothing getting in the way of rising stockmarkets or incredibly tight credit spreads.” That begs the question as to how investors can square these two ideas – or, as Gimber puts it: “How can we have such a complicated economic backdrop and yet markets painting such a rosy picture?”

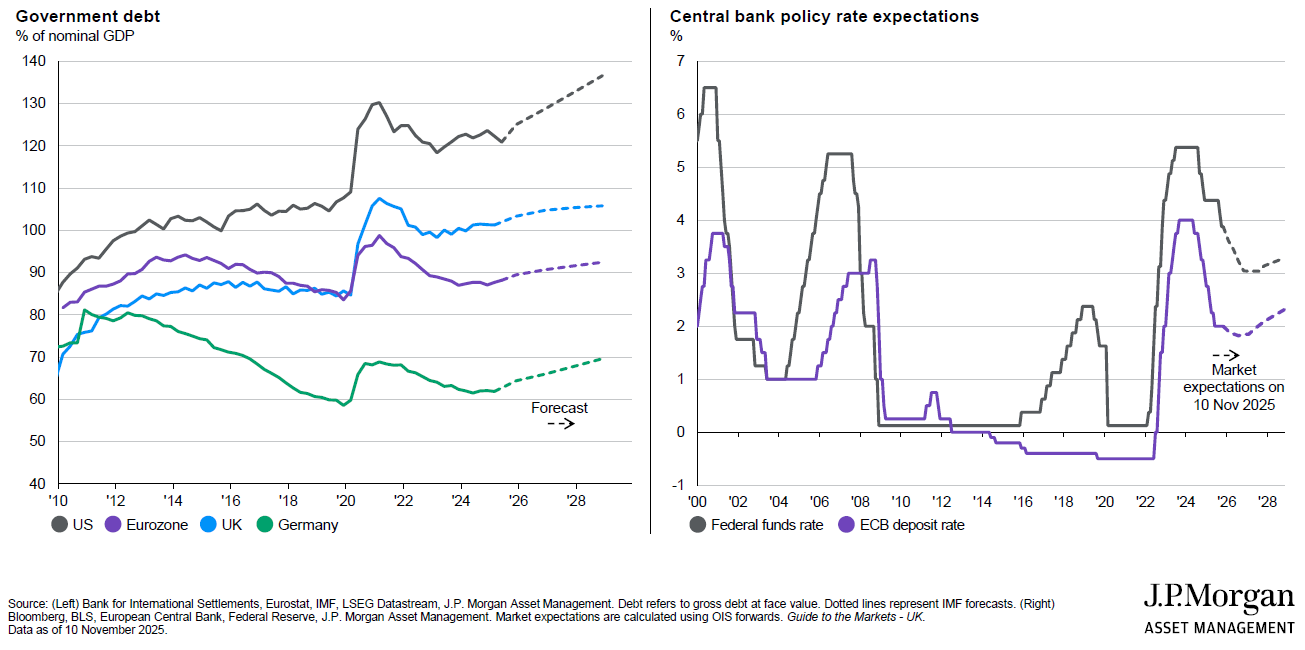

The answer, he believes, lies in government policy – both fiscal and monetary. Pointing to this next slide, he explains: “We are entering a new world, frankly – living through an economic experiment like nothing that has ever been seen before. Typically, if you are looking at deficits at these levels or the number of rate cuts markets are pricing in, you are either in the middle of a world war or deep in an economic recession.”

And no wonder with this much fuel being thrown in the engine

Instead, we have a global economy that “looks pretty resilient”, suggests Gimber, adding: “Does this economy need booming spending or lower interest rates, based only on a run of economic data? I think most people would say, No – why would central banks be thinking about taking rates down? Or why would governments be spending as if we are in the midst of a financial crisis when the economy is broadly holding up OK?

“Still, my job is to think about what is happening in the world – much as I might like to decide what happens! And, when you look at the increase in debt levels, this is pouring into people’s pockets. In the US this year, we have had the largest tax cut for the middle class on record. We have never seen this kind of experiment before – and the US administration is completely ignoring that debt-to-GDP is at 120% and heading higher.

Read ‘Part 1’ here: Hugh Gimber: What might upset risk sentiment in 2026?

“If you call your fiscal policy legislation ‘The One Big Beautiful Bill’, it suggests you are pretty confident you are doing the right thing. The US government is saying, Ignore the charts, we think the right thing to do is to spend – and spend more and more and more – to get our economy going and, importantly, to try and make people feel happier about the economic backdrop.” For Gimber, this drills to the heart of the matter.

“Electorates are feeling increasingly unhappy about the world and increasingly frustrated about how far their money stretches,” he argues. “So governments are having to say, Our way out of this – to try and win the next election – is giveaways. How much can we spend now to put people’s pockets in better shape so they might just vote for us again?” Nor is this boom in government spending any longer just a US story.

“Focus on the gap between the grey and green lines,” says Gimber. “For the past 15 years, the US has been spending but Europe – and Germany in particular – has been in balance-sheet repair mode. Back in 2010, most of these debt levels were between 75% and 85% but, whereas the US has risen to 125% today, Germany has been in fiscal-consolidation mode.

When governments spend …

“Arguably that gap between the grey and the green explains a lot of why Europe has performed so much worse, frankly, than the US economy – because the US government has been willing to spend while the Germans have not. Now, though, look at the forecast for where this is all heading: all the lines are moving in the same direction – and we see the fact Europe is now willing to spend as a really big deal.

“Fiscal stimulus works; monetary stimulus – on its own – does not. Just think about all the economic experiments we went through in the 2010s – with the European Central Bank (ECB), in particular, trying whatever they thought they could do to get inflation back to 2%. Did it work? No. But, when governments spend, that can really move economies.”

If fiscal policy is accelerating, inflation is above-target and growth is looking healthy enough, then central bank behaviour seems odd. “If you follow the economic textbooks, you would think they should be holding – or maybe even pushing rates higher,” says Gimber. “And yet, in the case of the ECB, we have already had 200 basis points of cuts while, in the case of the Fed, the path for US interest rates looks set to be lower over 2026.

“So this all feels like a pretty rosy backdrop. Risk assets are telling us, We like this level of stimulus; consumers are saying, We might not feel that happy about the world, but we are willing to keep spending. And, with the US in particular, there is effectively another round of stimulus to come when people receive tax rebates in the post next quarter. That should drive another leg of spending – and thus another leg of US economic growth.”

What sorts of risks, then, could accompany an “economic experiment” of this magnitude? “History teaches us excess stimulus can create inflation and asset bubbles – although, to be clear, I see these as tail-risks for 2026,” says Gimber. “Our base case is continued expansion, continued gains in equity markets and that bond markets are pretty fairly priced today – but there are key factors to track closely to ensure that optimism holds.”

Potential spoilsport #1: Inflation

First up among the potential spoilsports is inflation – and here Gimber’s focus is firmly on the US. “This is where we care the most because it sets the tone for the Federal Reserve,” he explains. “Provided the Fed can keep looking at the economy and say, Yes, inflation is above-target but don’t worry – we know we need to keep cutting, given the labour market – then risk sentiment should hold up.

“It is inflation rising and then becoming stuck at much higher levels that would give the Fed far more cause for concern – and indeed, when the tariff announcements were made back in April and May, if you had asked me for a forecast on where inflation would be now, I would have expected it to be at higher levels. Frankly, the pass-through of tariffs into US inflation has been much slower and much smaller than I would have anticipated.”

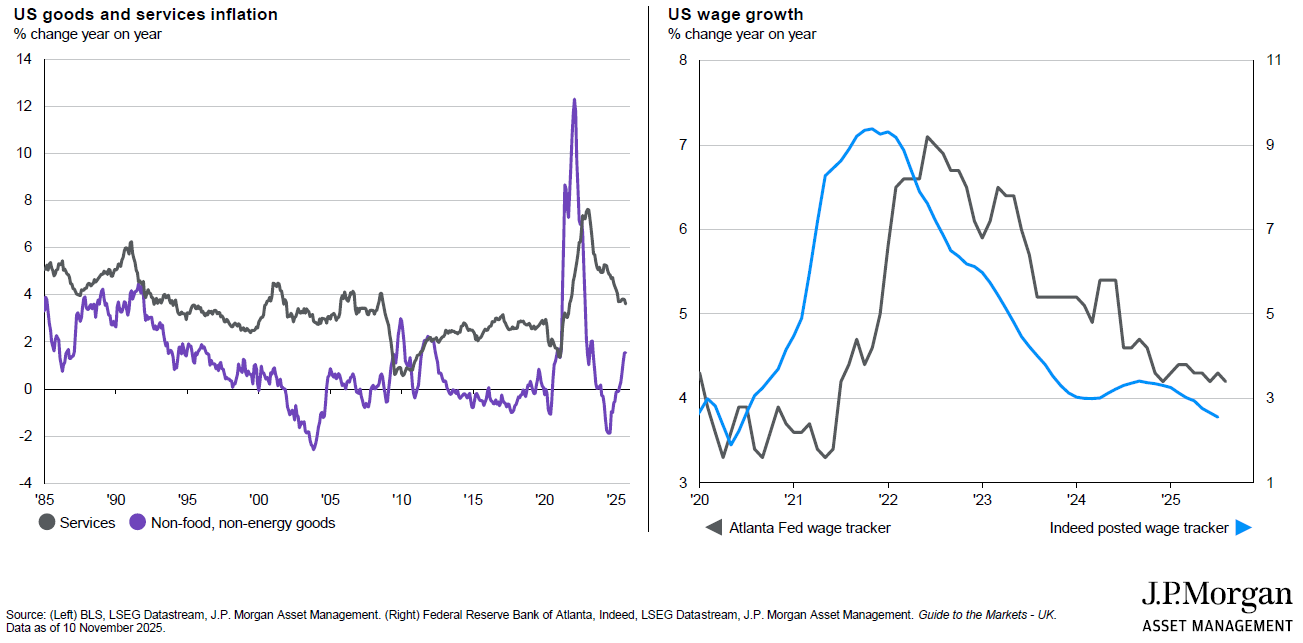

There are several reasons for this, suggests Gimber – the first being that, while goods prices may be picking up, they are being offset by slowing services inflation, as the lefthand chart below illustrates. Another is that Covid taught businesses to handle supply shocks better and, when they saw tariffs on the way in April, they frontloaded as many imports as possible over the first quarter to avoid having to pass through prices too quickly.

Risks of second-round effects appear under control for now

Third, US businesses are keenly aware that, if they announce big price rises, they risk incurring the disapproval of the White House and so are finding other ways to manage through, such as scaling back hiring or finding different supply-chain routes. Last and perhaps most significant of all, suggests Gimber, is the sheer volume of rule changes US customs officers will have had to keep up with this year – and thus what might get overlooked.

“As they stand, the rules would imply tariffs should be about a 16% tax on US imports,” he notes. “If we look at what is actually being paid today, though, that comes down to about a 10% level. So while I think US goods inflation will increase over the coming quarters, a moderation in services inflation and lots of the different ways businesses are handling this will likely keep inflation sub-4%.

“And for the Fed – provided the labour market remains on this cooling path – that is probably good enough but it is one of the key issues we need to track next year. Inflation at 4% for a few months and then coming back down to target is fine. Here the Fed could look through and say, We can write this off. We can keep moving rates lower because we know, by the end of 2026, we are going to be much, much closer to target.”

Self-fulfilling cycle

The big worry, warns Gimber, is the risk of inflation becoming embedded. “What would stop the Fed is if they start to see wages picking up,” he explains. “Wages are the link that makes this more dangerous because, when people see higher prices in the shops and so demand higher wages, they end up with more money in their pocket, businesses think they can hike their prices again – and you have this self-fulfilling cycle of inflation.”

Still, for Gimber it is “So far, so good” on wage inflation. Referring to the righthand chart above, he explains the grey line is the official data from the Atlanta Fed while the blue one is gleaned from Indeed jobs websites. “When businesses put salaries in their job advertisements, they give people like us really useful information because, as you can see, the blue line is generally a few months ahead of the grey one,” he says.

“So we do think inflation is picking up – but what we are seeing in the labour market suggests this is just a tail risk. It is not a central scenario of spiralling inflation next year because wages, which are the key link that would make us more worried, remain under control so far. That said, I suspect this ‘US wage growth’ chart will be going into our next ‘Guide to the Markets’ pack as one of the most important data-points to track through 2026.”

This is an edited version of the first half of the keynote speech Hugh Gimber, global market strategist at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, presented to the audience of Wealthwise’s Autumn Wealth Forum on 13 November 2025. You can read the second half – on the risks posed by bond vigilantism and capital misallocation – here while J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s 2026 Investment Outlook ‘Fuel in the Engine’ can be found here