“Things tend to be liquid when you don’t need liquidity – and just when you need liquidity most, it tends not to be there.” Howard Marks, Oaktree Capital

Few ideas have taken hold in modern investing as firmly as the belief that illiquidity is a virtue. Private equity, private credit, private infrastructure – all are sold on the premise that locking capital away creates superior returns and stability. This is a dangerous myth.

Illiquidity does not eliminate risk – it hides it. It allows complacency, gives managers cover and leaves investors trapped when mistakes inevitably occur. What looks like low volatility is usually just infrequent pricing – and the longer the lock-up, the greater the opportunity cost.

Liquidity is not a luxury for short-term traders. It is the discipline that forces transparency, accountability, and adaptability. It is, in truth, the real premium investors should value.

Just last week, Bloomberg reported the Bank of England was preparing to stress-test the private credit market, reflecting mounting regulatory unease over its rapid growth and opaque risk.

The move signals a broader recognition that, while private credit has boomed on the back of higher yields and limited scrutiny, its underlying vulnerabilities are still largely untested. It is a timely reminder that even policymakers are beginning to question whether the supposed stability of illiquid assets might, in fact, be masking the next source of systemic fragility.

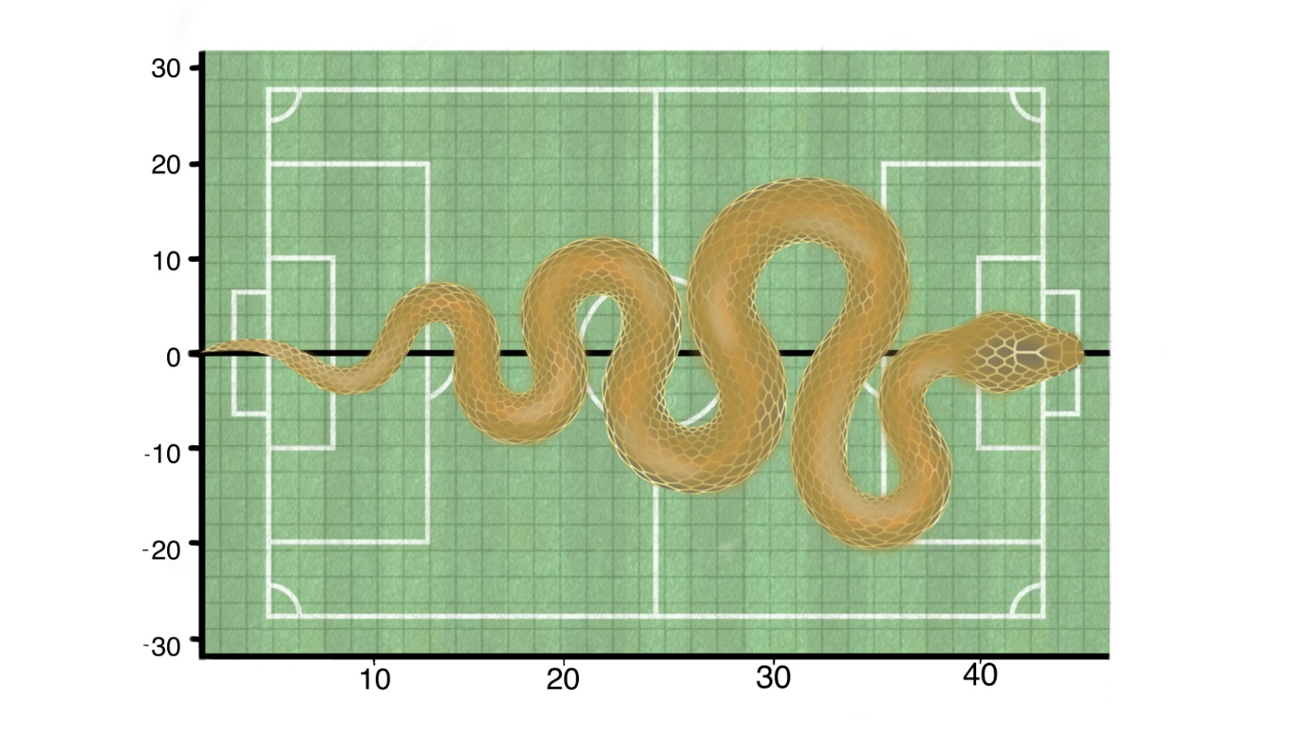

The mirage of low volatility

Ask any allocator why they like private equity or private credit and you will hear the same refrain: strong returns, low volatility, diversification. Scratch beneath the surface, however, and you find that much of the ‘low volatility’ is a mirage.

Private funds mark portfolios quarterly – sometimes even less frequently – using models and appraisals that smooth out the bumps. Compare that to daily-dealing liquid funds that mark to market every day. Which one looks smoother? The answer is obvious.

Yet smoothing does not mean safety – it simply hides the volatility until it comes crashing through. In downturns, the mask slips, valuations gap lower, defaults spike, exits vanish. The supposed diversifiers suddenly behave a lot like the public markets they were meant to hedge.

Independent research from Harvard, Bain, and Cliffwater suggests that, once returns are de-smoothed and adjusted for stale pricing, private equity’s true correlation with public equities lies around 0.7 – far higher than headline figures imply. That is not diversification – that is equity beta, leveraged and fee-laden, masquerading as something different.

Then there are the costs. The ‘2 & 20’ model is alive and well in private equity and debt. Add in fund expenses, transaction fees, monitoring fees and carried interest and investors can be paying 3% to 5% a year in drag. You need a stellar manager just to break even versus public markets.

And let’s not ignore dispersion. The gulf between top-quartile and median private equity managers is more than 15% annualised, according to the 2024 McKinsey Global Private Markets Review. Miss the top tier and you risk a decade of underperformance, locked away in assets you cannot exit.

“What looks like low volatility is usually just infrequent pricing – and the longer the lock-up, the greater the opportunity cost.

Liquidity is often dismissed as a nice-to-have. In reality, it is everything. Being trapped in an underperforming private fund for seven to 10 years is the very definition of opportunity cost.”

That is the brutal truth – the risk of permanent capital loss in private markets is real. Studies show a quarter of funds fail to return committed capital net of fees. Yet investors continue to pile in, seduced by the promise of double-digit internal rates of return that may never materialise.

Liquidity is often dismissed as a nice-to-have. In reality, it is everything. Being trapped in an underperforming private fund for seven to 10 years is the very definition of opportunity cost.

And let’s be honest: lock-ups are great – but they are great for the managers, not necessarily for the investors. They guarantee the fund a captive pool of capital, steady fee income, and freedom from redemptions, regardless of performance. For investors, they remove the one thing that matters most in a fast-changing world: the ability to adapt.

When better opportunities appear elsewhere, capital is trapped. When portfolio companies face refinancing cliffs, you are stuck. The optionality to de-risk or hold cash simply is not there. That is the real opportunity cost.

It is often argued that family offices and large pension funds are perfectly placed to invest in illiquid assets – after all, they have permanent capital, long horizons and can accept lock-ups in ways retail investors cannot. The real question is not whether they can tolerate illiquidity, however – it is whether they should.

Illiquidity has another effect too – it allows complacency. Managers can hide behind it. Poor marks or bad decisions do not show up in daily NAVs, so mistakes remain buried until much later. That may suit the managers – it certainly buys them time – but it does not serve the investors.

Family offices may believe they can live with lock-ups, but liquidity still matters. Private equity and private debt may seem clever and superior but one simple mistake – and we all make them – can last for years. Add to that the opportunity cost of being trapped when better options emerge, and the poor value that comes from paying high fees for opacity and you have to ask: is it really worth it?

Daily-dealing liquidity is not just about short-termism. It enforces discipline, transparency and accountability. It makes mistakes visible quickly, so they can be managed. That is a far healthier framework for long-term wealth preservation than illiquidity disguised as sophistication.

Private credit – calm waters, hidden currents

Private credit’s narrative is seductive; steady income, floating rates, low defaults. But its boom has coincided with one of the most benign credit backdrops in history.

According to data from PitchBook, Preqin and McKinsey, global private credit assets have surged from roughly $550bn (£412bn) in 2014 to more than $2tn by 2023, with forecasts suggesting they could exceed $3tn by 2028. McKinsey’s Global Private Markets Report 2025 highlights the continued institutional pivot toward private markets – not just through traditional commingled funds but via separate managed accounts and co-investments, which are quietly accelerating growth.

Family offices have joined the rush. UBS data shows allocations to private debt doubled from roughly 2% to 4% in 2023, and six in 10 family offices looked to increase exposure further in 2024. Anecdotal evidence suggests this trend continues in 2025. The logic is understandable: higher yields, lower mark-to-market volatility, and the appeal of something that feels differentiated.

But that calm surface hides powerful currents. As the cycle turns, highly levered borrowers face rising costs and weaker covenants. Defaults will climb, recoveries will fall. The same opacity and illiquidity that smoothed performance on the way up will more than likely magnify losses on the way down.

The industry has a short memory. Every cycle brings a new ‘must-own’ alternative – and more often than not, disappointment follows. Hedge funds, for example, were the darling of the pre-GFC years. Capital poured in, fees rose, performance lagged and redemptions surged just when they were needed most.

For their part, catastrophe bonds have seen waves of inflows every time spreads widened, only for hurricane seasons to wipe out years of coupons. Mezzanine finance promised juicy yields right before credit cycles turned and recoveries evaporated.

Today’s fad is anything with the word ‘private’ attached. Private equity. Private credit. Private infrastructure. The inflows are extraordinary. Like every fad, though, too much money chasing too few opportunities leads to weaker terms, inflated entry prices and lower forward returns. Investors chasing the illusion of high returns with low volatility risk setting themselves up for the same disappointment as every fad before it. We have been here before.

Cyclical amnesia amid the boom

The golden age of private markets was built on cheap money, rising valuations and abundant liquidity. That era has ended. Higher rates, record dry powder and tougher exits point to lower returns ahead. Dispersion will widen; opportunity cost will grow heavier. And yet capital continues to flood in.

Investors are still chasing yesterday’s story. When asked what investors learned from the global financial crisis, legendary value investor Jeremy Grantham replied: “In the short term, a lot. In the medium term, a little. In the long term, nothing at all. That would be the historical precedent.”

This ‘cyclical amnesia’ is as much a feature of markets as liquidity itself. The collective tendency is for investors to forget past pain and any lessons learnt – just as the next herd gathers pace and safety in numbers begins to cloud judgment.

And yet not all ‘alternatives’ are created equal. Think, for example, about what liquid absolute return can offer investors. Daily liquidity. Transparent pricing. Diversification across genuinely uncorrelated strategies. Explicit risk controls. The ability to hedge, rebalance and adapt in real time.

Liquid absolute return and multi-strategy funds do not hide risk – they manage it. They mark to market daily, accept short-term volatility and manage it with discipline. The outcome? Smoother, more consistent returns that investors can actually access.

Daily pricing makes risk visible – and visibility makes people uncomfortable - but honest volatility is far safer than hidden fragility.”

It is curious, then, that liquidity – the one feature that offers flexibility, transparency and control – is so undervalued. Investors still flock to illiquid asset classes that promise ‘stability’ but deliver opacity and inflexibility instead. Perhaps it is because daily pricing makes risk visible – and visibility makes people uncomfortable – but honest volatility is far safer than hidden fragility.

As I have argued many times in this column, liquid alternatives deserve far more attention than they receive. They offer access to the same sophisticated strategies – long/short equity, macro, event-driven, market-neutral – without the lock-ups, opacity or fee drag of private structures. In short, they give investors what even the best private funds cannot: liquidity, adaptability, and genuine diversification.

Private equity, private debt and other illiquid assets will always have a place – at the right time – in a well-diversified portfolio, but their promise of stability is too often an illusion. Fees are high, risks are hidden and lock-ups benefit managers more than investors. Even family offices and pensions, with permanent capital, should ask themselves whether illiquidity is worth the risk.

By contrast, UCITS liquid alternatives may look less glamorous, more regulated, more transparent – even a little boring, perhaps – but that is precisely their strength. The investor protections embedded in UCITS, combined with daily liquidity and independent oversight, provide something private markets cannot: control, accountability and confidence.

When the next cycle turns, liquidity will pay dividends. And those ‘boring’ UCITS structures may prove to be the smartest and most resilient alternatives of all. Not all alternatives are created equally – and the sooner investors accept that, the stronger and more flexible their portfolios will be.

The structures evolve, the narratives grow smarter, and the rationales become ever more compelling, yet behaviour never changes. It may be the most quoted line in investing, but Sir John Templeton’s warning remains the simplest and truest of all: “The four most expensive words in the English language are: this time it’s different.” Only time will tell, but at this point, I am not willing to risk it, so will continue to favour ‘boring’ liquid alternatives.

Ian Willings is a portfolio manager and partner at Apollo Multi Asset Management, experts in researching and investing in absolute return and liquid alternative strategies. CIO, Steve Brann, is the author of Absolute Vision, a book that sets out the thinking behind the firm’s strategy and looks to demystify the asset class for a wider audience. The team manages the Apollo Diversified Multi-Strategy Fund, a daily dealing UCITS portfolio designed to deliver steady, uncorrelated returns through a blend of quality liquid alternative managers.