Last Friday (12 September), Fitch downgraded France’s sovereign rating from AA- to A+. The agency justified this decision on the grounds of a persistent deficit, public debt already at 114% of GDP – and likely to reach 132% in 2034 – and chronic political instability.

At this level, France is approaching Italy’s ratios, which are expected to reach 135%, while diverging from economies such as Spain and Belgium, whose trajectories appear more stable. This downgrade does not place France in a situation of immediate crisis but it does confirm a perception of relative weakness.

The downgrade can also be explained by the continuing deterioration in budgetary balances. Since 2017, tax revenues have fallen by 1.6 percentage points of GDP for households and 0.8 percentage points for businesses, without being offset by a reduction in public spending.

Public spending remains high, representing 57% of GDP compared with an average of 50% in the eurozone – a level comparable to that of 2017 after peaking during the pandemic. The primary deficit remains below the threshold for stabilising debt. An analysis of the spending surplus compared to the rest of the eurozone (7 percentage points of GDP) shows most of it comes from the pension system (2.2 percentage points) and healthcare (1.5 percentage points).

“These institutional weaknesses fuel the perception of France as a peripheral country within the eurozone, rather than a semi-core pillar.

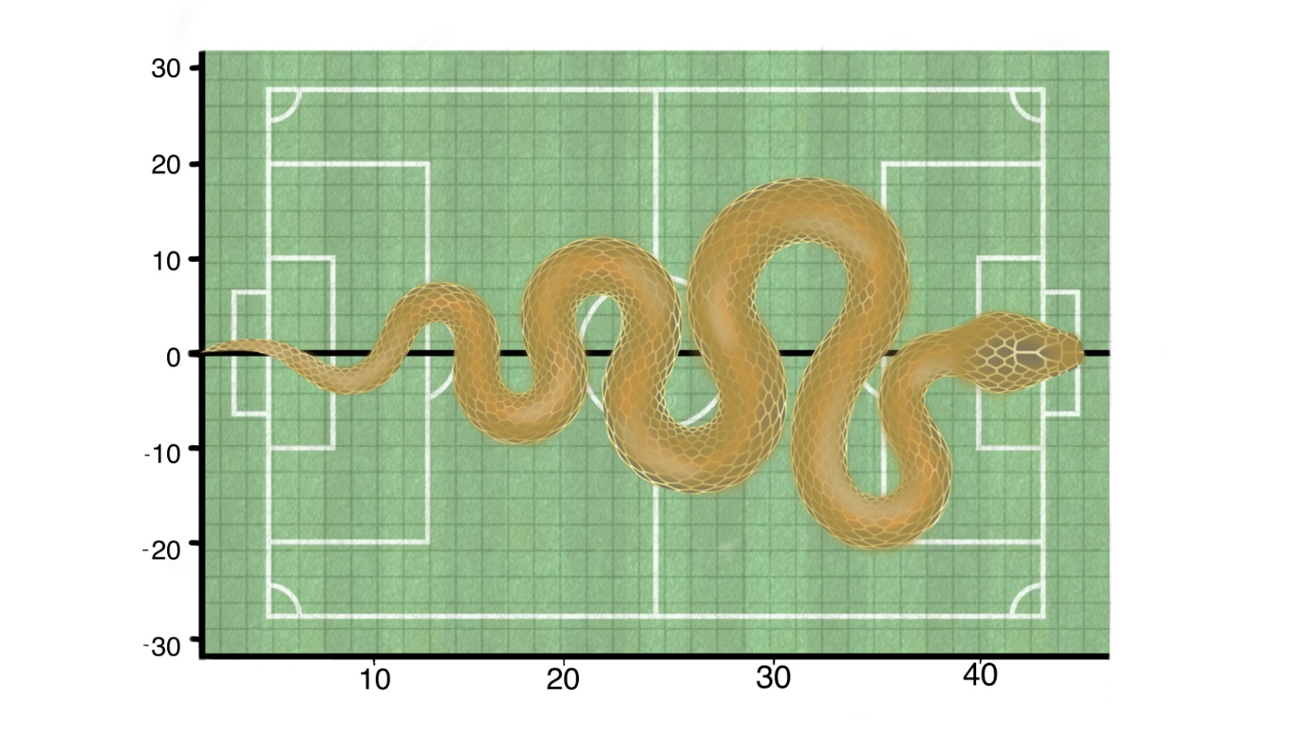

The most notable development does not concern the 10-year yield, but rather the widening spread with 30-year bonds”

The problem lies in the fact this sanction seems set to continue. After the fall of the Bayrou government and the arrival of Sébastien Lecornu at Matignon, the parliamentary deadlock persists. In the absence of a solid majority, the prospect of the dissolution of the National Assembly appears increasingly inevitable.

The inability to build a credible consensus around the budget reinforces the idea that France will not return to a clear consolidation path anytime soon. These institutional weaknesses fuel the perception of France as a peripheral country within the eurozone, rather than a semi-core pillar.

Technical factors

Bond markets are reflecting this downgrade without panicking. The yield on 10-year French government bonds (OATs) is around 3.5% – slightly above Greece and close to Italy. The rise in borrowing costs reflects an increased risk premium but remains well below the levels seen during the sovereign debt crisis. French debt continues to be considered good-quality by most investors.

The most notable development does not concern the 10-year yield, but rather the widening spread with 30-year bonds – reflecting a steepening curve that is often interpreted as a sign of inflationary concerns. Long-term expectations have remained stable, however.

This movement mainly reflects technical factors: a structural reduction in demand from pension funds and insurers; demographic dynamics reducing the need for very long-term securities; and market saturation due to sovereign bond issues.

Investors have tended to favour ‘steepener’ trades to position themselves on the spread between five-year and 30-year yields, taking into account all of these technical factors, which affect all sovereign debt, and also expressing their doubts about France’s fiscal trajectory. In this context, where safe-haven assets are under pressure, flows are shifting towards gold and even investment-grade credit, which remains in demand despite its credit spread reaching historically low levels.

"Several large French groups, including Airbus, Axa, L’Oréal and LVMH, are now borrowing at lower rates than the government."”

Indeed, a major shift is taking place in the debt market hierarchy as several large French groups, including Airbus, Axa, L’Oréal and LVMH, are now borrowing at lower rates than the government. The contrast highlights both the confidence placed in these companies and the pressure exerted on sovereign debt by excess supply and the massive volume of public debt issued.

Points of resilience

This picture does need to be qualified. France has several strengths: a current account balance that is close to equilibrium – in contrast to the massive deficits of Greece and Spain before 2008; a high household savings rate of 19%, which provides a solid domestic cushion; lower inflation than its neighbours; and the ECB’s safety net, via its Transitional Protection Programme, which is designed to prevent excessive fragmentation of the eurozone.

It should also be noted the risk of contagion to the rest of the eurozone remains very limited. France’s problem is primarily political, not financial –it is not a bankrupt state likely to drag down its neighbours.

Even if the National Rally were to win, the impact would remain limited due to the probable absence of an absolute majority and European safeguards. The Italian example shows spreads can remain orderly despite the arrival of a government perceived as radical. Finally, the mere mention of the European Stability Mechanism by the ECB would probably be enough to calm any excessive tension on spreads.

Fitch estimates the deficit will exceed 5% of GDP until 2027, pushing back any consolidation until after the presidential election. This trajectory is already largely priced in by the markets. France is losing its status as a semi-core pillar and is now considered peripheral in the eurozone – however, it is not entering a crisis zone.

The higher risk premium is now the new normal, absorbed by investors in a context where credit and alternative assets continue to attract massive flows. It is the risk of a new dissolution that will once again weigh on French debt.

Michaël Nizard is head of multi-asset and overlay at Edmond de Rothschild Asset Management