If I am being completely honest, it seems unlikely there is a great deal of intellectual overlap between me and the economics Nobel Laureate and behavioural psychology legend that is Daniel Kahneman. Nevertheless, we do seem to have been on the same page on the effectiveness of shouty teachers – and, with all due modesty, I was onto it much earlier in my life than him.

Sure, there may have been a few minor contextual differences. At some point in the mid-1970s, I was in the gym of a provincial Hampshire boarding school shivering in my shorts as I was berated for my inability to, say, execute a half-decent forward defensive – or maybe even a half-decent forward roll – thinking miserably to myself, ‘How can this possibly be helpful?’

For his part, at roughly four times my age – albeit a decade earlier – Kahneman was in what some might see as the rather cooler situation of advising air force instructors on effective techniques for training fighter pilots and thinking to himself, ‘Hey, this could be a seminal moment in the study of mean reversion and decision-making. Maybe I could one day write a book about it and call it Thinking Fast and Slow.’

OK, so those may not have been his exact thoughts but I do know Kahneman spotted something the berated and beshorted me did not. As you may well be aware, the story goes that having suggested the instructors try encouraging their young charges rather than shouting at them, Kahneman was told the current system worked very nicely, thank you, because whenever a pilot was shouted at for a mistake, they did better the next time.

Seller’s remorse

Conversely, should a pilot be praised for good performance, they tended to do worse the next time – therefore, the instructors felt, ‘Shouting = good; Praise = bad’. So far, so boarding-school but what Kahneman realised was , while the instructors’ observations were correct, their conclusion was not. Positively or negatively, the pilots were demonstrating regression to the mean – a concept the instructors did not understand.

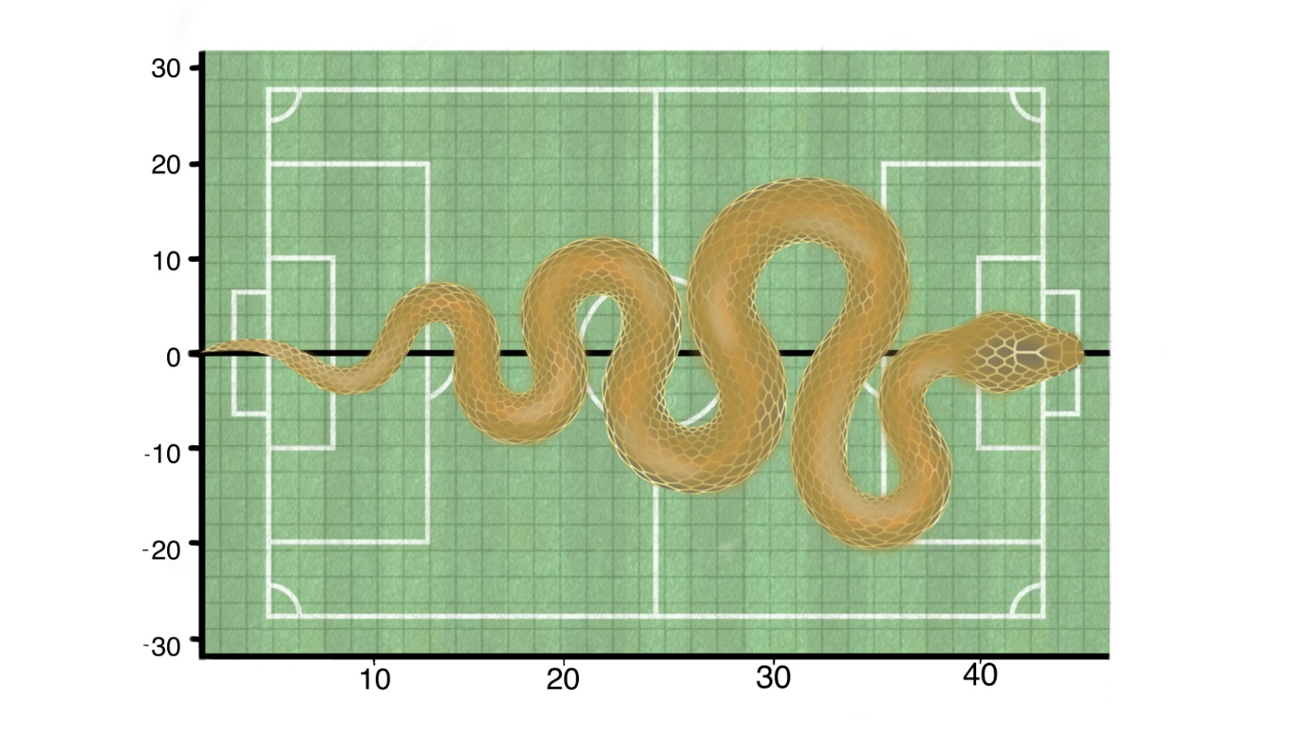

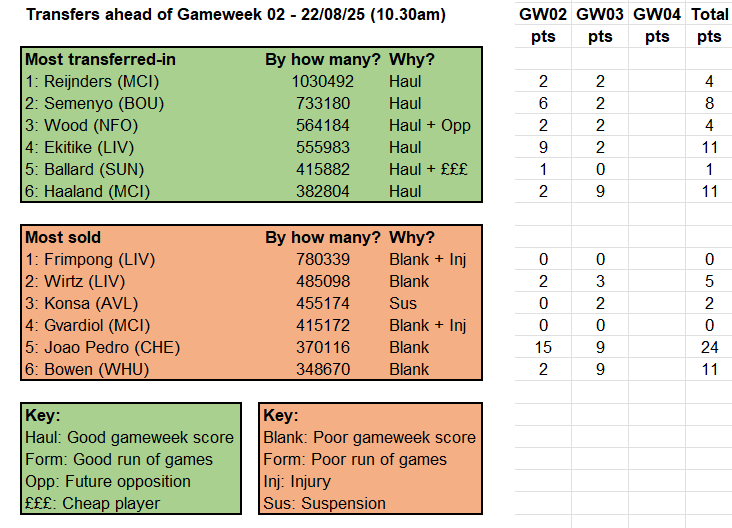

Which brings us neatly to the serious business of fantasy football and the big buying and selling trends of the first three weeks of the season. One strand of Mean Reversion Machine’s dual mandate is to keep close tabs on the footballers who are most transferred in and out of squads by Fantasy Premier League’s millions of players – and the positive or negative effects this might have had on their points totals in the following weeks.

As Peter Snow used to say on election nights back in the 80s and 90s while bouncing around in front of graphics almost as spurious as the one below, ‘It’s just a bit of fun’. And yet even in these early weeks of the season, we can see evidence of herd behaviour and of potential buyer’s and seller’s remorse – most prominently Chelsea’s Joao Pedro, who has returned 24 points since 370,000 people sold him after his GW01 two-pointer.

“One theory runs that anything that is an imperfect measure of skill, such as athletic performances, does eventually regress to the mean. I guess ‘eventually’ may be the operative word there.

The nine points West Ham’s Bowen bagged in GW03 is likely to have stung too but, in general, the herd will be feeling reasonably sanguine about its first fortnight of heavy selling. Less so, perhaps, about the early-season buying bandwagons, though, with only the nine points each from Haaland of Manchester City and the aforementioned Joao Pedro offering any sort of immediate gratification.

And you read that right – after 370,000 sold the latter after GW01, almost double that number bought him after his second-week haul. Looking ahead, it will be interesting to see when Bournemouth talisman Semenyo starts rewarding the 2.5 million and counting who have bought him since GW01 finished. Given the amount of shots he takes per game, the law of averages would suggest one has to go in sooner rather than later.

For my own part, meanwhile, I will be hoping Aston Villa’s Watkins and Liverpool’s Wirtz – two players who feature prominently in the transferred-out tables and expensively in my own FPL team – start to enjoy their own upturns in fortune. Both have had disappointing starts to the season but, fortified by this column, I keep telling myself they know how to kick a football and … well … you know regression to the mean and everything.

Dynamic explanations

Incidentally, while that Kahnemann anecdote has become a classic of behavioural psychology, he and long-term collaborator Amos Tversky never offered any actual data to support it. In 2006, though, in ‘Regression to the mean in flight tests’, US economists Reid Dorsey-Palmateer and Gary Smith did precisely that, using US Navy flight training data to demonstrate there is substantial mean reversion in trainees’ performances.

The pair found that, while the pilots’ performances during training tended to be inconsistent in the short term, they did improve over time – and, as they did so, they reverted to the mean. Interestingly for my hopes for Watkins and Wirtz, one theory advanced here is anything that is an imperfect measure of skill, such as athletic performances, does eventually regress to the mean. I guess ‘eventually’ may be the operative word there.

Dorsey-Palmateer and Smith go on to offer three reasons why people struggle to grasp the idea of regression to the mean: “First, they do not expect regression in many situations where it is bound to occur. Second, as any teacher of statistics will attest, a proper notion of regression is extremely difficult to acquire. Third, when people observe regression, they typically invent spurious dynamic explanations for it.”

Just imagine if I had been able to explain that all to my PE teachers – assuming, of course, I could get a word in edgeways. Then again, they still had corporal punishment back in those days.